“All right, he’s sick. He’s full of misery and fear. He was dangerous, and could be again, though I doubt it. But that boy has known a passion more ferocious than I have felt in any second of my life. And let me tell you something: I envy it.”

DISCLAIMER

This post is weird and might (definitely) piss off some people. Sorry.

I just thought it was an interesting mental gymnastics topic. Please do not interpret this as my attempt to create some sort of Hatsune Miku Mickey Mouse Clubhouse horse banging cult.

Oh and there’s nudity by the way. And gore.

On November 4th, 2018, 35-year-old Akihiko Kondo married his decade old-lover, Hatsune Miku. Their wedding cost over 2-million-yen and was heavily adorned with a whole banquet hall packed with grooms, witnesses, and reporters. Kondo brought his Miku plush and life-sized Miku doll, and the whole nuptial was about as professional as any other “normal” wedding would be.

Religiously, weddings have always been perceived as one of the holiest things a human can experience: a union of two individuals under the eye of God. And from a social standpoint, weddings are the foundation of families and the building blocks of society. With that in mind, Kondo’s marriage would appear to be a perversion of both paradigms. Religiously, he married an inanimate object, and socially, he… well… married an inanimate object (go figure!). Yet, despite this obvious deviation from the sacred Normal, in many ways, Kondo’s matrimony is, without a doubt, religious. He’s committed himself into a monogamous relationship that he views as his higher purpose in life just as—if not more than—most theistic individuals.

After their sacrament, Kondo even took Miku on a honeymoon and booked plane tickets and hotel rooms for two people. He is devout. He has faith in Miku in an identical way as Christians have faith in God. And just like any devoted Christian, Kondo, too, finds purpose in his God.

Prior to finding Miku, Kondo describes his life as miserable, constantly being labelled a weirdo and bullied at his workplace. But upon discovering Miku, Kondo beats his depression, stating “[Miku] lifted me up when I needed it the most. She kept me company and made me feel like I could regain control over my life.”

Miku saves Kondo, and when Kondo’s at his lowest, it’s Miku whom he finds faith in and relies upon, and fundamentally, Miku fulfills that hole in Kondo’s life just as religion fulfills the hole in billions of others. She guides him in life to become a better person. She gives him assurance and answers in his darkest times. And most of all, she doesn’t harm him. Even a professor from the University of Manitoba says that “having a partner who is safe and predictable is often very helpful therapeutically.” There’s no denying that Miku isn’t exactly your typical orthodox god, yet she still serves the same function as religion: something to have faith in. And this common theme of faith is prevalent everywhere.

I’ve never been a huge Disney fan. I enjoy their movies and think their characters are appealing, but I can’t exactly say that I’m religiously in love with the company. I’ve been to Disneyland once in my life and that was it. Yet, to millions of other people, Disneyland is a modern Mecca.

On November 19th, 1989, a Los Angeles Times article about Disneyland was published, discussing Disneyland’s similarities with religion. The research was done by two Boston researchers, Christopher and Debra Parr, Disney fans, who found their visits to Disney akin to a church.

“It begins with the huge parking lot that has tall signs painted with cartoon characters—presumably to help you remember where your car is parked. Or do the signs say that “Goofy, Pooh Bear and Dumbo are the seraphim who will watch over your wheels while you’re within the shrine?”

This quote proposes that there is a solace found in Disneyland akin to that of a church. And just like how Christians go to church on Sundays, Jews celebrate Shabbat, and Muslims visit Mecca, Disney fans too, are compelled to make their annual pilgrimage to the quote-on-quote “happiest place on Earth”—or in the Parrs’ words: “[a park that] is secluded, walled off from the ‘profane,’ an island of harmony, order, peace. The distinct religious message… is that the future will bring happiness, as in the song, ‘When You Wish Upon a Star.’”

Almost all religions are about that star, with most religions promising that despite the often bleakness of everyday life, there is a heaven waiting after death—a star in the sky far away from the burdens of Earth. In that sense, Disney fans visiting Disneyland to go on their favourite rides and meet their favourite characters for the promise of escape directly parallels Christians visiting church on Sundays and praying to God for the promise of heaven.

Connecting this back to Kondo, it’s safe to say that both he and other Disney fans can relate in the fact that they all have found devout faith and solace in something that isn’t just orthodox religion. Both have found promise and assurance in their own God, and nowhere is this creation of personal gods more distict—and extreme—than in Peter Shaffer’s 1973 play, Equus:

DYSART: Yes. There’s a sea—a great sea—I love… It’s where the Gods used to go to bathe… The old ones. Before they died.

ALAN: Gods don’t die.

DYSART: Yes, they do.

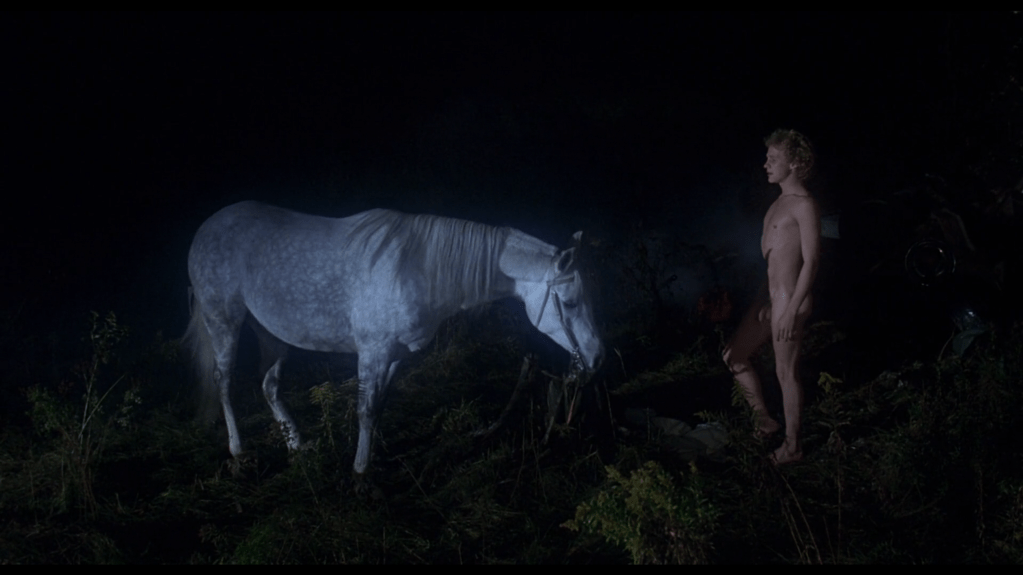

Equus is one of the most uncomfortable things I have ever read, and the synopsis alone is enough to make most people gag. The play follows Dysart, a psychiatrist, recalling memories of his time treating a boy named Alan. Alan is, well, not normal. He’s forced to meet this psychiatrist because he worships horses, wants to have sex with them, and eventually stabs them in the eyes.

From Alan’s viewpoint, he perceives horses as a concept of God that he calls Equus: Equus the Kind, the Friend, the Merciful. And throughout Dysart’s process of treating the boy, he uncovers deep memories of Alan and unravels events that caused the boy to become the way he is. Yet, in this supposed healing process, Dysart reaches an epiphany that although the boy does suffer from many underlying issues such as family trauma, his infatuation with Equus is true and his passion, beautiful. Overtime, Dysart begins to sympathize with the boy and understand that he was “born into a world of phenomena all equal in their power to enslave him.”

Alan is passionate, but his passion is not normal, so he’s punished by the world as such, thereby forcing Dysart into facing a great dilemma: he can either let Alan be who he is, pursuing his religious devotion to Equus, or return Alan to the great Normal, essentially killing Equus in the process and Alan’s self-realized purpose to live. And it’s in this dilemma does Dysart begin questioning the Normal:

“The Normal is the good smile in a child’s eyes—alright. It is also the dead stare in a million adults. It both sustains and kills—like a god. It is the Ordinary made beautiful: it is also the Average made lethal. The Normal is the indispensable, murderous God of Health, and I am his priest. My tools are very delicate. My compassion is honest. I have honestly assisted children… I have talked away terrors and relieved many agonies. But also—beyond question—have cut from the parts of individuality repugnant to this god, in both his aspects. Parts sacred to rarer and more wonderful gods.”

In the eyes of Alan, Equus is God: a god he created and obeys, a god who gives him purpose in life, a purpose and passion much stronger than any in Dysart’s life as while Alan leads his life with freedom and love, Dysart is stuck in a passionless marriage and toxic occupation where he is forced to slay the gods of children because that’s what society expects of him as a psychiatrist.

As much as Equus explores Alan—the abnormal’s—fanaticism, the play also just as much explores Dysart—the Normal‘s—enslavement of individual freedom. Dysart knows that his job is to murder passions and gods. Dysart knows that his job is to “save” Alan. And Dysart knows that if he does not sacrifice Alan to the Normal, then his job, reputation, and anything and everything he has ever known will be smited away by the great Normal.

In the end, Dysart chooses himself over Alan. He cures Alan of his abnormality, but does so while cognizant of the atrocity he has committed. In his final lines, he criticizes psychiatry in his philippic:

“In an ultimate sense I cannot know what I do in this place—yet I do ultimate things. Essentially I cannot know what I do—yet I do essential things. Irreversible, terminal things. I stand in the dark with a pick in my hand, striking at heads! I need—more desperately than my children need me—a way of seeing in the dark. What way is this?… What dark is this?… I cannot call it ordained of God: I can’t get that far. I will however pay it so much homage. There is now, in my mouth, this sharp chain. And it never comes out.”

One thing that I haven’t discussed yet regarding creating one’s own god and religion is the fact that people can very realistically be harmed. Religion has always been one of humanity’s greatest passions. There’s constant discussion about religion, people constantly find division and unity through their beliefs, and wars are repeatedly started over different ideas of god. People like Kondo are no different, really. About a year ago, the company that supplied him with the technology to talk to his virtual wife stopped supporting software for Miku, rendering Kondo destitute, unplugged from his wife. In the case of Disneyland, there’s the bitter truth that everything around you is heavily commercialized and the god-like imagineers who design the “happiest place on Earth” are also constantly attempting to devour your wallet at every turn. And in Equus, Alan is very obviously sick and in perpetual agony. But at the same time, this pain is also what gives these gods purpose and authenticity, and as Dysart puts it:

“To go through life and call it yours—your life—you first have to get your own pain. Pain that’s unique to you. You can’t just dip into the common bin and say ‘That’s enough!’… [Alan’s] done that. All right, he’s sick. He’s full of misery and fear. He was dangerous, and could be again, though I doubt it. But that boy has known a passion more ferocious than I have felt in any second of my life. And let me tell you something:

I envy it.”

In the words of many journalists and Akihko Kondo himself, Kondo is described as a “fictosexual,” which according to Dictionary.com, “is used in the context of a person who is sexually or romantically attracted to a fictional character, especially when it involves a strong emotional attachment.”

I dislike this definition. In fact, I dislike the word as a whole—or at least the concept of it, because in Kondo’s own simple words, “what I have here is definitely love,” so why complicate it?

At the end of the day, Kondo worships his idea of God religiously and that’s really all there is to his relationship. It sucks that his love is dependent on a random tech company, but nevertheless, his passion for Miku still remains stagnant. It sucks that his own mother rebukes his marriage, but ultimately, it’s Kondo’s own pain that Kondo himself has created and therefore has to deal with. Kondo has created his own God, his own passion, his own pain, and I think that we can all agree that not many people can actually match his level of faith.

Over the past few decades, religion has been on decline with less people being theistic as science and war provoke more to begin doubting the existence of a just God. Yet, the idea of God remains the same. The modern gods are not some divine being up in the clouds, promising heaven and threatening hell. No, the modern gods are the celebrities we obey, the companies we pray to, and more, more, and more, for in the end, there is no line separating God, passion, and Hatsune Miku.

Leave a comment