“If you look at any kind of intractable conflict between people or peoples, at some point you’re gonna find somebody doing something because of love. That love manifests as fear, hatred, xenophobia, racism, [and] religious superiority”

In an interview with Vulture, co-creator of HBO’s The Last of Us, Craig Mazin, received a question that he interpreted as “what is the cost of love,” to which he responded, “[i]f you look at any kind of intractable conflict between people or peoples, at some point you’re gonna find somebody doing something because of love. That love manifests as fear, hatred, xenophobia, racism, [and] religious superiority.” Admittedly, this quote is a gross oversimplification of The Last of Us, but it’s nevertheless accurate. Every arc in the show depicts characters pushed into the extreme due to love, and the whole series is one massive buildup to Joel finding his life’s purpose within Ellie before choosing that purpose over the world itself. Likewise, Bill and Frank are no exception to this cynical theme of love, passion, and meaning.

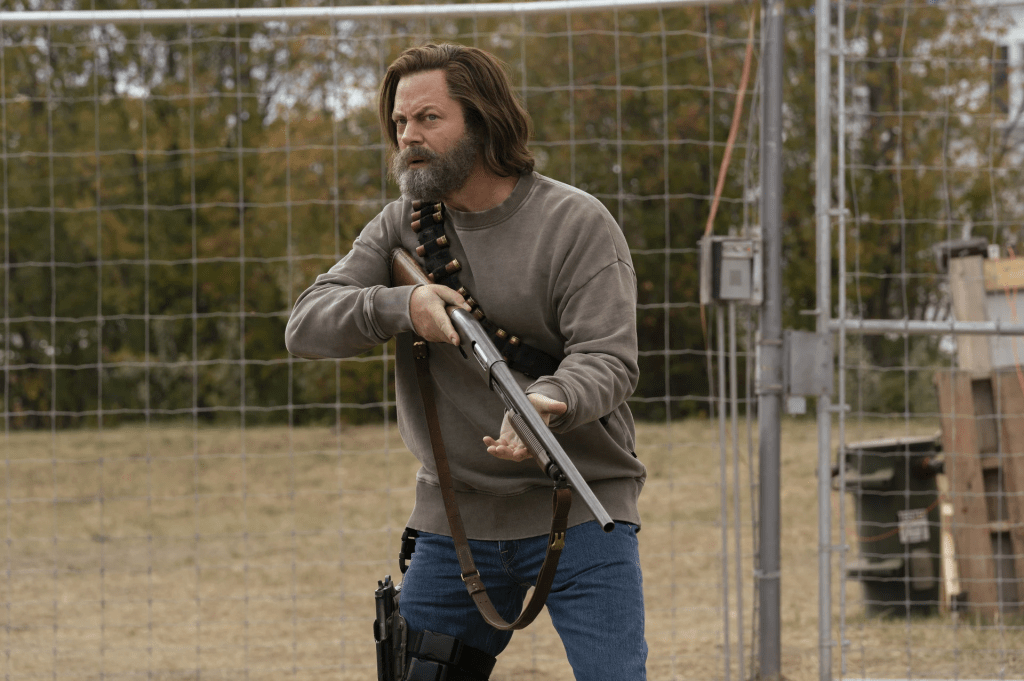

In contrast to the rest of the apocalyptic world, Bill’s fortress is safe and peaceful thanks to his skepticism towards the government and—more importantly—his loneliness and rejection of love. As an apocalypse prepper, Bill lives alone, secluded from the rest of society, and although his community looks for him at the start of the outbreak, he adamantly chooses to segregate himself, doubtful of the world. As a result of this choice, Bill lives lavishly as the rest of his community dies. He has food, he has water, he has oil, land, shelter, weapons, wine, and more important than what he does have, is what he doesn’t: fear. In a scene in which an infected walks up to Bill’s fortress, he turns on the television to watch as the purportedly dangerous infected gets its head blown to smithereens before Bill scoffs and takes a bite of his steak, entertained by the violence and impressed by his ingenuity. By virtue of his isolation, Bill lives in paradise, immortal to violence and fear—that is, however, until he meets Frank.

The initial confrontation between Bill and Frank serves as a reminder to the audience that Bill is still in the apocalypse. The scene is anxious, and Frank’s intentions are ambiguous; his actions could be devious, words deceitful, and smile… deceptive. Cautious as he is, Bill understands this too. He helps Frank out of the hole, but chooses to maintain safe distance, pointing his gun at him while never turning his back to Frank… yet the next scenes start showing the contrary.

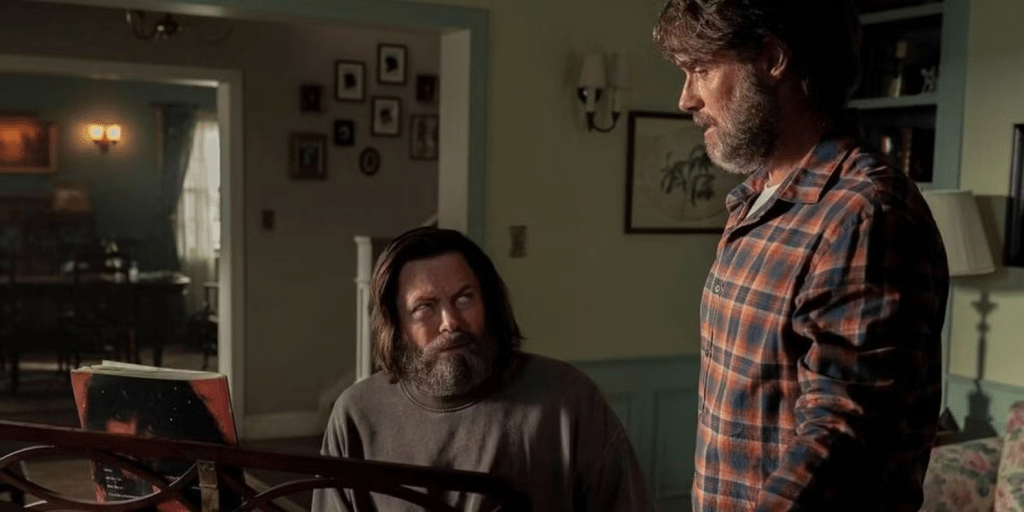

When Frank takes a shower, Bill isn’t there to supervise him, and when Frank waits for his meal, Bill isn’t there to make sure that Frank doesn’t run off. The restless tone still dominates these scenes, but simultaneously, Bill’s seemingly character-defying (in)actions begin to compound into one central idea that even in the apocalypse, even when everyone is struggling to survive and dependence on others equates to weakness, trust and solace can still be found, and this idea is most prevalent in the piano scene.

Bill’s entire existence mocks the apocalypse. Others struggle to find resources, but not Bill; Bill’s got unlimited food, safety, and comfort. While he fortifies his property, the songs that accompany him are “I’m Coming Home To Stay” and “White Room,” two rock songs that basically taunt the eerily atmospheric soundtrack of the rest of the show. The piano, however, juxtaposes both the rest of the world and Bill’s fortress. In an apocalyptic world where people fight everyday for food, there is no room for the piano, and in Bill’s pragmatic fortress where everything serves a practical function, the piano sticks out like a sore thumb because it represents something that has no right nor purpose to exist in the world of The Last of Us: ART, and equally as incongruous as the piano’s existence in the apocalypse is Bill’s zealous appreciation of it. When Frank asks Bill about the piano, Bill says that it’s worth “currently nothing,” but as Frank begins butchering “Long Long Time” Bill repulses, and in reaction, abruptly stops Frank as if to suppress the artistic frustration inside of himself—but Frank pulls him in. He tells Bill to play, and Bill does the unbelievable: he turns his back. And what ensues is my favourite scene of anything of all time.

I remember watching this scene for the first time. I remember there was one particular shot that explicitly framed Frank standing tall while looking at Bill’s exposed and vulnerable turned back. I remember thinking about how this scene directly inverts their initial encounter of Bill looking down on Frank in the hole. I remember fear—thinking to myself that this was Bill’s mistake and his moment of peripeteia in which upon turning his back and showing vulnerability, he commits taboo in regards to both the apocalypse and his personal set of cautious values, and Frank will surely now bring down his scythe, punishing Bill for growing lax… But once the music started and first three chords played, I knew immediately that everything will be alright.

The apprehensive tone doesn’t stop with the piano scene, because while the fear that Frank will betray Bill disappears, it’s immediately supplanted by a fear far greater than betrayal: the fear of loss.

When raiders siege Bill and Frank’s home, the scene isn’t scary because raiders are attacking, it’s scary because Frank might lose Bill.

When Bill and Frank share strawberries, the scene is just as beautiful as it is tense because the fear of loss is eternal whilst the sweetness of the berries, temporary.

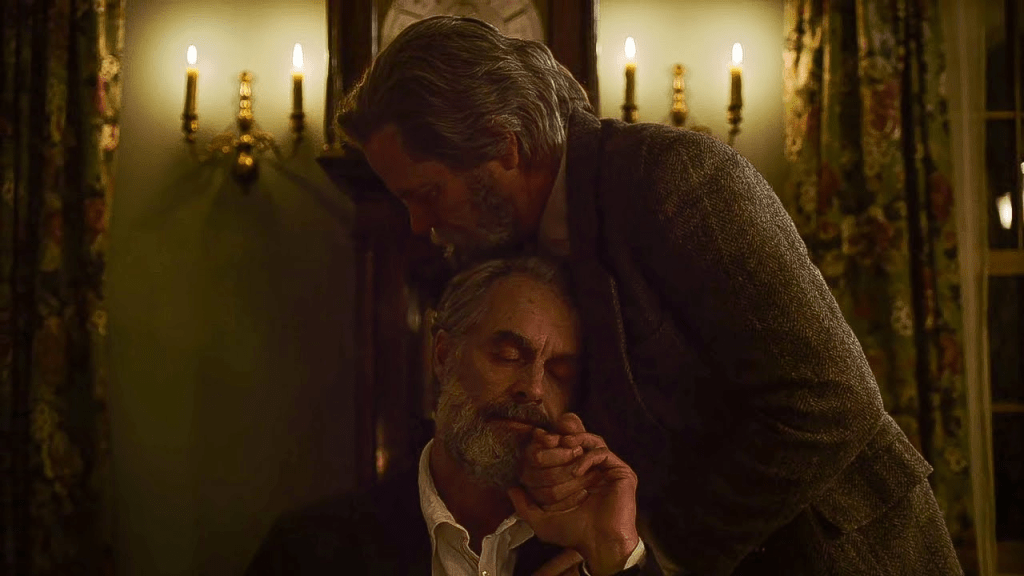

And when Frank becomes terminally ill, the fear of loss becomes a reality more real than ever. Bill’s vulnerability is no longer just his back, rather, that vulnerability has manifested itself into something far rarer and fragile: a lover. And in the end, faced with losing his love, Bill chooses to commit suicide alongside Frank, an act that should technically end all possibility of future purpose in their lives, but given the transformation of their deathbeds into their wedding beds, serves in actuality to give meaning to their lives through their deaths.

Corroborating this post-mortem purpose, the last shot of the episode zooms into their turquoise room, adorned with plants and art, comforting the audience by telling them that Bill and Frank have left their mark and are in a better place now overlooking Joel and Ellie. Of course, there is no guarantee of heaven, and for all anyone knows, the death of Bill and Frank marks the end of their times together along with any hope of finding purpose in the future; nevertheless, the leaves will eventually fall, flowers will wither, paint will dry, and people will die. Thus, to Bill and Frank, there’s no better way to rebel against this absurd and impermanent world than by celebrating one’s existence no matter how temporary those celebrations may be.

Beauty, love, and passion create anxiety, tension, and fear, but regardless of whether you’re struggling everyday to survive or you’re living lavishly like Bill, death is inevitable, and although it serves as the end to all memories and purpose in life, its impending presence paradoxically gives life its meaning by assuring a conclusion to everybody’s story.

Thanks for reading.

Afterward

This post is just a segment of a larger essay. I figured the complete essay was a bit too long for anyone to read, so I posted this shorter and ever-so-slightly edited version, which I think includes all the key points without yapping too much. Anyways click here if you’re interested in the complete essay.

Leave a comment