“The absurd is the essential concept and the first truth.”

Table of Contents

Plague

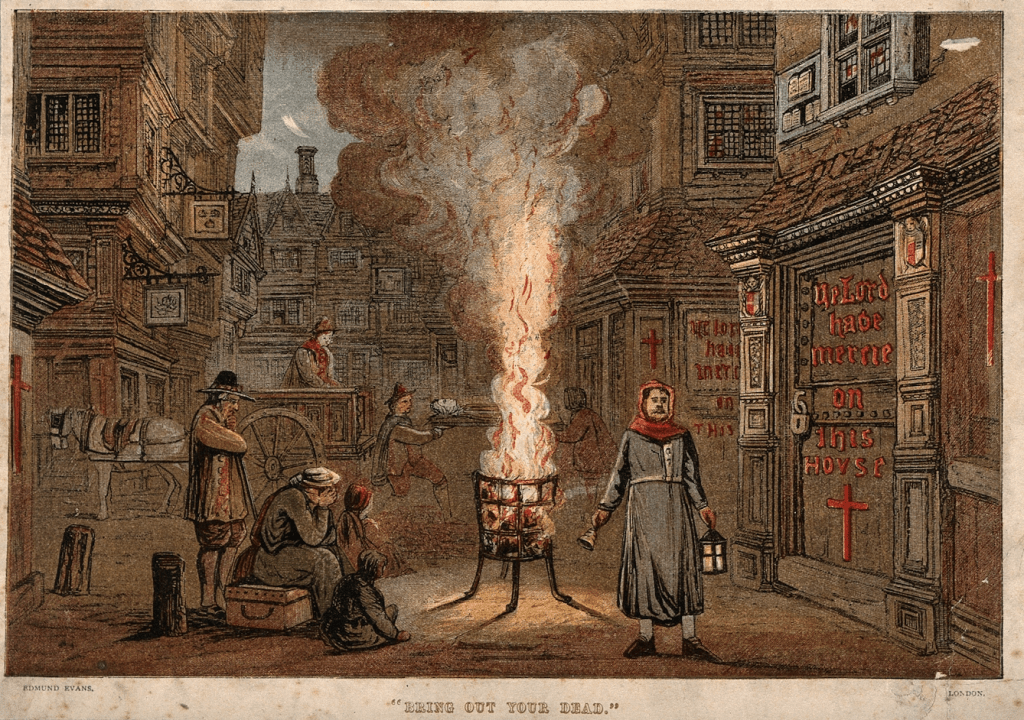

After wiping out around half of Europe in the 1300s, the bubonic plague returned for a second round in what would be called the Great Plague of 1665. Ironically—or maybe unironically—despite the three century-gap, the citizens of 1650s London responded to the upheaval in a similar fashion to their Middle Ages counterparts: some chose to help the needy, others turned to religion for solace, a bad bunch sold snake oil for a quick pound, and the remaining were probably dead or dying. Naturally, in this pursuit for a logical answer in a seemingly illogical disaster, everyone began resorting to superstitions:

Smell! It’s the smell that kills. No! It was because the wells were poisoned by the Jews! No! Bad humours, it’s always bad humours! Wrong! I’m telling ya, it’s the cats and dogs. Kill ‘em all! Wait, no! It’s sin, the trumpets are booming, horsemen descending, angels singing, Revelations is upon us, and God is here to punish all!…

I think there’s one word that captures this period perfectly: absurd. An absurd time period, occupied by absurd people, responding in an absurd manner to an absurd disease. And in terms of this recurring absurdity, there’s no symbols as apt as the cross of St. Roch, more commonly referred to as the red cross or plague cross which, during the Great plague, was used to identify households of the infected. Brazenly, red and black crosses would be painted across civilian doors, signaling neighbors to beware and informing medical personnel that “hey! There’s a family in here that needs to be monitored and assisted…”

… But in reality, the plague cross was more like a headstone if anything. Oftentimes, those being quarantined would be abandoned and left to rot without medical care or food or water as their home slowly transforms into their grave.

Generally, humans don’t like to think of themselves as a heartless species that’d condemn each other to death, and so, immoral acts like the plague cross would commonly be polished up so as to become easier to turn a blind eye to. In Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel, A Journal of the Plague Year, he reported that in the regulations of the Lord Mayor of London, it stated that “every house visited [with the disease] be marked with a red cross of a foot long in the middle of the door, evident to be seen, and with these usual printed words, that is to say, ‘Lord, have mercy upon us,’ to be set close over the same cross, there to continue until lawful opening of the same house.” This quote can be read in two ways: the lines “Lord, have mercy upon us” and “until lawful opening of the same house” create a sense of uplifting hope that fate is on our side and bound to provide eventually… but given the frequent abandonment of these homes, that hope becomes nothing but an opioid that promises the sick that heaven is waiting after death while assuring the rest of society that God will clean up the mess—so there are some people you can desert.

Of course, giving those believers the benefit of the doubt, what the hell else were they supposed to do in a world predating modern medicine and germ theory? If hope allows them to willfully live and peacefully die, then why not hope? I dunno about you, but if someone told me I was gonna die in a few weeks and then proceeded to offer me molly, you best believe I’m going out in a bang!

Nevertheless, the plague cross stands testament to how humans react to the unknown: by overdosing on these opioids of voluntary ignorance while settling for not the best, but the most convenient answer. However, even in this absurd world where answers to prayers lie only in the afterlife, there are still answers in the physical world—not in the idealistic, abstract realm, but in the rugged, imperfectly beautiful physical world as seen in the relationships of The Last of Us.

Sarah

Sometimes it is easier to see clearly into the liar than into the man who tells the truth. Truth, like light, blinds. Falsehood, on the contrary, is a beautiful twilight that enhances every object.

The Fall, Albert Camus

Unlike Europeans of the Middle Ages, characters of The Last of Us are lucky enough to have a more explainable cause for the outbreak, which, with the help of sCiEnCe, is deduced to be caused by cordyceps. But despite this superior understanding, the people of The Last of Us still react in a near-identical, absurd fashion to their Middle Ages counterparts of seven centuries ago.

When the outbreak hit Texas, it didn’t appear in some extravagant, grandiose way—it just… happened. And with this underwhelming entrance came not the fear of zombies but fear of the unknown. Sarah isn’t scared of the infected—she doesn’t even know they exist yet—rather the things that startle her most are-

-the flashing lights outside, national alert on the TV, helicopter, blood on the floor, neighbor is acting weirdly, uncle Tommy shoots my neighbor, wait no, Dad kills her instead, now Dad’s a murderer, I’m in the back seat, Dad runs people over, sirens, we’re on the highway, it’s a virus, is it from terrorists, Dad doesn’t know, I might be sick, people, panic, plane, crash.

The whole sequence is irrationally, illogically, unreasonably, ludicrously, unpredictably absurd. Just that same day, Sarah was living a normal life; her biggest struggles were focusing in class, fixing her dad’s watch, and making sure he gets his daily vitamins. In contrast to this content lifestyle, the night after just seems too absurd to even comprehend, and too-absurd-to-even-comprehend it is.

Both The Last of Us’ medium and contents seemingly reject the thought of a world-altering event. On the radio, Sarah and her family hear of a disturbance in Jakarta only to ignore it, and when Sarah picks out a film, we see a supposedly immoble old lady behind her squirm, yet the camera blurs her out, opting to focus on the more normal Sarah instead because the prospect that an old, paralyzed lady on a wheelchair could suddenly revitalize and become a monster is just too absurd for anyone—even the camera itself—to consider. But no amount of denial will change reality, and the price of the world’s voluntary denial of the absurd is the world’s equally absurd reaction to the outbreak.

The price is the confusion. The price is the panic. The price is Joel having to frantically carry Sarah, his daughter—his sole purpose in life—while running away from… whatever a clicker is. The price is a seemingly heroic soldier swooping in to save Joel and Sarah, only to have that same saviour be her executioner as well.

The absurd is the confusion; it’s the futility of searching for reason and purpose in an incomprehensible universe devoid of order or meaning; it’s indifference, injustice, lawlessness, despair… and inescapable.

Riley

Nothing can discourage the appetite for divinity in the heart of man.

The Rebel, Albert Camus

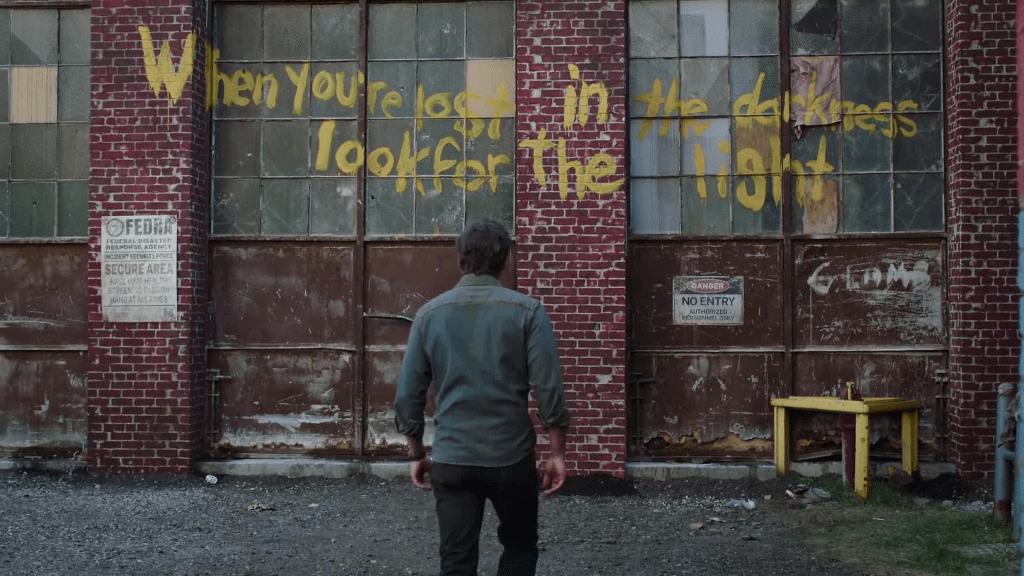

One of the most ubiquitous lines repeated in The Last of Us is the slogan of the Fireflies, “when you’re lost in the darkness, look for the light,” an optimistic quote that promises answers much like the religious doctrines preached during the plague. And much like religion during the plague, the Fireflies, too, deny the absurd and present themselves as a pillar to lean faith upon. Their holy grail is to discover a cure for the infection, which, given the context that the infection symbolizes the indifference of the world, acts as a metaphor for challenging the absurd. When Marlene first talks to Ellie, Marlene tells her that “you have a greater purpose than any of us could have ever imagined,” revealing Marlene’s creed to include innate essence in people that dictates their purpose in life. She, the leader of the Fireflies, believes that existence precedes essence, and it’s this tenet that enables her to see the Fireflies not as terrorists, but missionaries, destined to create paradise on Earth.

The slogan, “when you’re lost in the darkness, look for the light” is in every way, religious. “Darkness” and “light”: a juxtaposition connotatively associated with religion as in John 8:12 “[w]hen Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.’” Proverbs like these implore listeners to put faith in their preachers, and put faith in, they do. When FEDRA, the primary governing force of the world, assigns Riley to be a sewage worker, she loses faith in her future and life as a whole. She is in the darkness; however, Marlene shows her the light. She sees Riley’s talents and ideologies and translates that into her purpose by offering her an escape, an identity, and an essence. In response to this seemingly irrefusable offer, Riley puts her faith in the Fireflies, a group which she now believes to be her higher purpose, higher than her and Ellie’s relationship—a relationship that’s authentic and real and truly exists in the physical world.

“They chose me. I matter to them,” Riley says, and yet at the end of her life, the Fireflies are absent. Confronted with death, Riley no longer needs the escape the Fireflies offer as those irresistible promises of a higher purpose are vain in the face of death. What isn’t vain, however, is Ellie, who fights for Riley, and while Riley loses faith in the Fireflies, her faith in Ellie remains stagnant because Ellie is truly there, authentic and right in front of her. The Fireflies’ cause might not be attainable or even real for that matter, but Ellie’s lips sure are.

Henry

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.

The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

Between The Last of Us game and show, Henry’s last words transform from “Henry, what’ve you done” and “it’s all your fault” in the game, to “what did I do” in the show—each version reflecting Henry’s compunction from killing his brother Sam. “What did I do” expresses Henry’s flood of confusion and self-blame. He could be honestly asking how he failed to protect Sam, he could be genuinely confused about the incomprehensible act of shooting one’s brother, or he could also just be posing a rhetorical question because there is no single right answer or response to his action. All interpretations are possible—all interpretations are valid. As for the game, Henry’s perspective jumps out of his body: “Henry, what have you done… It’s all your fault,” he condemns himself before pointing the gun at himself and firing.

In the game, Henry and Sam are on the run because they walked into another group’s territory. In the show, Henry and Sam are on the run because Henry sold out a member of his own resistance. In both media, Henry and Sam are unwanted in the world except to each other, a fact especially true in the show in which Sam’s deafness leaves Henry the onus of communicating and caring for him, and it’s this unbreakable bond that warrants Henry jumping to third- and second-person as he disconnects himself from himself because he no longer has a purpose to exist. A world without Sam is a world without Henry, and likewise from Henry’s perspective, a world without Sam is no world at all. So he surrenders to the absurd.

Fever; delirium; vomiting; boils; swollen, painful buboes: these are just some symptoms of the bubonic plague. The symptoms would last from a few days to a few weeks, and to end this agonizing torture, Europeans would sometimes choose to euphemize themselves under the pretense that death is impending and inevitable. But it wasn’t for Henry. Henry was physically healthy; he had Joel and Ellie to accompany him, and Joel even directly tries to quell Henry’s impulsive state.

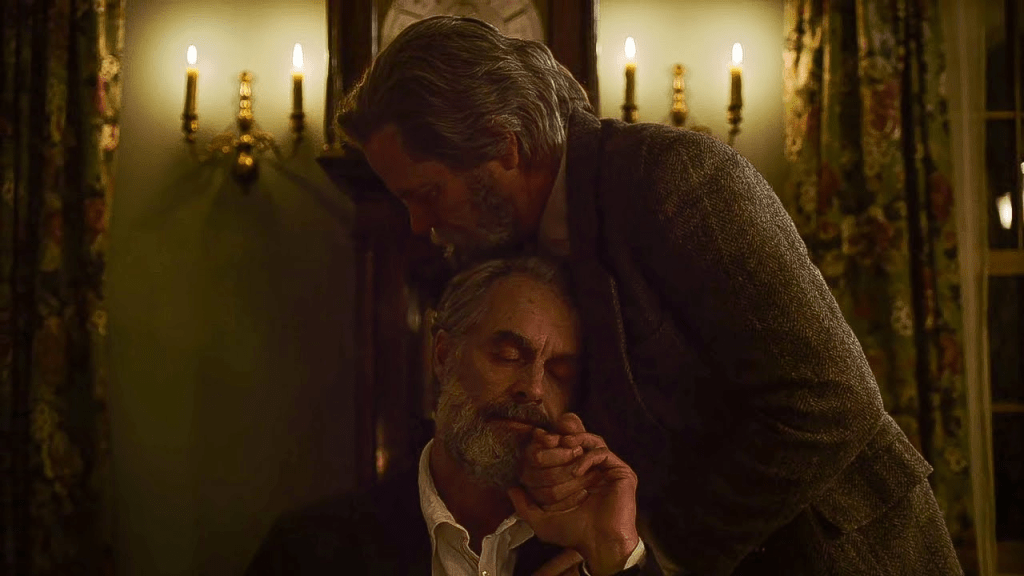

“Easy, easy,” Joel says in an attempt to pacify Henry. With Henry’s gun pointed at him, Joel doesn’t tell him to put it down; instead, he says, “give me the gun,” to protect Henry from himself, because Joel, having lived the past two decades in a world of absurd hopelessness, is fully familiar with suicide and Henry’s raving emotions. The dynamic between Joel and Ellie and Henry and Sam are blatantly similar; however, more similar to Henry’s familial relationship is that of Joel and Sarah’s. Akin to Sam, Sarah is blood-related to her guardian, she’s far less self-sufficient than Ellie, and she serves as life’s purpose for her protector, which leaves Joel and Henry as doppelgangers: both guardians of someone special, and both failures in that same regard, except while Henry succeeds in his suicide attempt, Joel fails, and it’s owing to this failure does Joel discover new purpose in life through Ellie. But Henry never finds his Ellie, as by escaping the absurd, Henry robs himself not only of his own life, but also his freedom to create meaning and purpose to live for.

David

From the moment that man believes neither in God nor in immortal life, he becomes “responsible for everything alive, for everything that, born of suffering, is condemned to suffer from life.” It is he, and he alone, who must discover law and order.

The Rebel, Albert Camus

“And I saw a new heaven and a new Earth. For the first heaven and the first Earth were passed away. And I heard a great voice out of heaven say, ‘Behold… the tabernacle of God is with men. And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes… that there will be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither will there be any more pain… for the former things are passed away.”

Despite their conflicting ideologies, Kathleeen, Marlene, Henry, and Joel are all akin to each other in regards to their immorality. They are thieves, liars, traitors, murderers, and more, more, and more; however, it would be erroneous to label them as amoral. Kathleen, leader of a resistance group, murders innocent people in her quest to avenge her brother, Marlene chooses to break her best friend’s dying wish for the betterment of the world, Henry backstabs his beloved leader to save his brother, and Joel commits countless upon countless acts of torture and murder both reactively and proactively to survive and protect those around him. All are immoral, but all also have their reasons… the same cannot be said for David.

David is everything listed above: thief, liar, traitor, murderer, but unlike the aforementioned characters, David indulges himself in these unscrupulous acts. A motiveless malignity, he psychotically worships violence itself with ferocious rationality and challenges the very definition of human nature, love, and evil.

Contrary to every other character who sees the outbreak as an agent to chaos and pain, David greets the carriage with open arms: “What does cordyceps do? Is it evil? No. It’s fruitful, it multiplies, it feeds and protects its children, and it secures its future with violence if it must. It loves,” desiring only to propagate in the physical world, in stark contrast to humanity’s quest for higher meaning in the metaphysical realm. David doesn’t need God, and in that sense, David is the ultimate absurdist who understands and embraces the animalistic nature of humans. However, as a pragmatist, he also recognizes the innate societal desire for God and solidarity.

“They need God, they need heaven, they need- they need a father.”

During the bubonic plague, religion was an opioid, but nevertheless, the opioid existed for a reason. It seems wrong for the church to promise heaven as a means to nullify society’s guilt of abandoning the sick, but that’s the whole point: religion—God—is supposed to help people move on, find solidarity, and create moral principles in a moralless world. Although the plague could’ve been treated better if people just collectively decided to work together in perfect unity and efficiency, that’s not just how people work. People are selfish, but just as much as people are innately selfish, people are also ironically constantly longing for a community to belong, and religion fills this hole for billions. Sometimes, due to an uncontrollable lack of resources, the sick did have to die for the greater population, and between dying with no certainty of the future or dying under the assumption that heaven is waiting, one scenario does sound profusely less grim than the other. Maybe religion tells lies, but more often than not, they’re lovely, practical lies. David, too, is a liar whose lies act as the foundation for his followers’ solidarity. Although lying about cannibalism is immoral by Christian standards, David’s followers are ignorant; his young follower Hannah doesn’t know she’s eating her own father, but what she does know is that there’s food on the table, and she’s not gonna starve. However, David’s lies extend beyond the altruistic intentions of providing solace and solidarity for his followers.

He lies to control.

After capturing Ellie, he tells her that “if you can’t trust me, then yes, you are alone,” presenting himself as pillar of faith and an equal to Ellie whilst revealing his true intentions to be carnal and his methods machiavelli. Hannah has food on her table thanks to David’s lies, but more importantly to David, he has food on his. In David’s lodge, boldly plastered on a large, hanging cloth is his slogan, “when we are in need, he shall provide,” and while the quote is supposed to mean God’s omnipotence, in practice, the slogan’s true function is to reinforce to David’s status as God himself. “I know you think you don’t have a father anymore, but the truth is, Hannah, you will always have a father, and you will show him respect when he’s speaking” David commands the grieving Hannah, agonized by the death of her father. Adding insult to injury, right after his philippic, David sits at the same table as Hannah and her mother, usurping the seat of Hannah’s father, one of the authentically meaningful relationships in her life. Beyond unifying people, David steals meaning from the lives of others for his own control and power. Compared to all other characters of The Last of Us, David’s understanding and acceptance of the absurd is peerless. But although there is an argument to be made that David is living in good faith because he finds purpose in the absurd through violence, it’s undeniable that his lies are ruinous and perverts and robs others of their freedom and meaning in life. In the abstract world, morality is nothing but a social construct, and there is no objective good or evil, but nevertheless, for stealing the fundamental right of people—their freedom and purpose—David is a sinner.

Joel

I rebel—therefore we exist.

The Rebel, Albert Camus

Throughout Joel’s journey to deliver Ellie, the two endure through treacherous environments teeming with infected and hostile human factions, yet at the end of their pilgrimage, their efforts weren’t celebrated and adorned with commemoration, but rather anticlimactic letdown. In the show, Joel and Ellie are walking, they get smoke bombed, Joel loses consciousness, then he wakes up to find Ellie gone. Likewise, in the game, the player doesn’t fight an action-packed battle against some sort of super-infected before meeting the Fireflies; instead, the gameplay is lackluster and consists exclusively of Joel and Ellie walking, swimming, pressing the triangle button to drop down a ladder. And after the underwhelming events of both media Joel wakes up alone in a lifeless, drab hospital room, juxtaposing the vibrant green scenery from just a moment ago. The mediocre tone of the whole ordeal disillusions Joel’s preconception of his journey. Before Tess dies, she begs Joel to “keep [Ellie] alive… and set everything right,” handing the mantle to him and transforming Joel’s run-of-the-mill journey into a holy pilgrimage that feeds into his preexisting narcissism by telling him that that it’s his fate and mission to restore the world with him as its saviour. But dropping ladders and getting smoke bombed disagrees with this idea of venerated fate and purpose.

Joel fought for Sarah, but now she’s dead; Joel fought for Tommy, but now, Tommy no longer needs a protector; and Joel fought for Tess, but now she’s gone; which leaves Ellie as the last bastion for Joel’s reason to be in the world, and Joel needs a reason to be. Without a purpose, he’s suicidal, he knows time won’t heal the void inside him, and he understands that Henry’s suicide upon losing Sam foreshadows his fate if he was to ever lose all faith in the world as well. Thus, Joel makes the selfish choice to rescue Ellie, kill Marlene, and rob the world of all hope for a better tomorrow. Ironically, before executing Marlene, Joel tells her that sacrificing Ellie for the world wasn’t a choice for others to decide and yet he decides Ellie’s fate for her, dragging her out of her tranquil slumber, revoking her martyrdom, and condemning her into into a world of beasts, rape, and death.

In the game, there’s a voice recorder that reveals Marlene’s confliction towards killing Ellie; Marlene believes that Ellie will be reunited with her mother in heaven, and Marlene chooses to spare Joel’s life under the belief that he will understand and forgive her for sacrificing Ellie. Likewise, Ellie also wishes to martyr herself for the world; her best friend and love-interest is dead, leaving her void of romantic purpose in the world and yearning for a poetic death. Both Marlene and Ellie find meaning in their sacrifice, and both Marlene and Ellie’s sacrifices are trivialized by Joel. Joel doesn’t want to save the world—the world’s taken everything from him—and to a certain extend, Joel doesn’t even want Ellie’s happiness—he just wants Ellie—and this cataclysmic passion leaves by far the most contentious question in The Last of Us: did Joel make the right choice?

The French existentialist philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, commonly used an anecdote he had with one of his students to answer these seemingly unanswerable dilemmas. In Sartre’s story, his student is perplexed between joining the French military to combat Nazi Germany who killed his brother or staying in France to care for his dying mother. Caught between a sense of duty to his nation and his family, the student goes to Sartre for answers, to which Sartre responds that there are no right answers because in the abstract world, no moral theory could possibly lead to a right answer; therefore, the correct choice is whichever the student chooses that aligns best with his chosen values. The choice is the answer.

By Sartre’s anecdote, Joel’s choice in the end was correct because it was truly authentic to him. Leading up to him “rescuing” Ellie, Joel mercilessly slaughters the Fireflies in a savage fashion that is nothing less than visceral: everything is inaudible except dramatic music and gunshots, and this unremorseful, machine-like killing spree leaves a trail of dead bodies and rubble. Joel is a violent person—this is a fact that’s been true for the entire show—thus the massacre only further attests to the authenticity of his choice and devotion to Ellie. But while Joel chooses to live in good faith by saving Ellie, she and the rest of the world are condemned to an endless hell of Joel’s selfish making. The world is absurd to Joel, and there is no paradise for him without Ellie, and so, he makes a choice that’s right to him and wrong to the world, but regardless of the irreversible extremity of either paths, Joel makes a choice and will forever live with its consequences.

Bill

The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

s “what is the cost of love,” to which he responded, “[i]f you look at any kind of intractable conflict between people or peoples, at some point you’re gonna find somebody doing something because of love. That love manifests as fear, hatred, xenophobia, racism, [and] religious superiority.” Admittedly, this quote is a gross oversimplification of The Last of Us, but it’s nevertheless accurate. Every arc in the show depicts characters pushed into the extreme due to love, and the whole series is one massive buildup to Joel finding his life’s purpose within Ellie before choosing that purpose over the world itself. Likewise, Bill and Frank are no exception to this cynical theme of love, passion, and meaning.

In contrast to the rest of the apocalyptic world, Bill’s fortress is safe and peaceful thanks to his skepticism towards the government and—more importantly—his loneliness and rejection of love. As an apocalypse prepper, Bill lives alone, secluded from the rest of society, and although his community looks for him at the start of the outbreak, he adamantly chooses to segregate himself, doubtful of the world. As a result of this choice, Bill lives lavishly as the rest of his community dies. He has food, he has water, he has oil, land, shelter, weapons, wine, and more important than what he does have, is what he doesn’t: fear. In a scene in which an infected walks up to Bill’s fortress, he turns on the television to watch as the purportedly dangerous infected gets its head blown to smithereens before Bill scoffs and takes a bite of his steak, entertained by the violence and impressed by his ingenuity. By virtue of his isolation, Bill lives in paradise, immortal to violence and fear—that is, however, until he meets Frank.

The initial confrontation between Bill and Frank serves as a reminder to the audience that Bill is still in the apocalypse. The scene is anxious, and Frank’s intentions are ambiguous; his actions could be devious, words deceitful, and smile… deceptive. Cautious as he is, Bill understands this too. He helps Frank out of the hole, but chooses to maintain safe distance, pointing his gun at him while never turning his back to Frank… yet the next scenes start showing the contrary.

When Frank takes a shower, Bill isn’t there to supervise him, and when Frank waits for his meal, Bill isn’t there to make sure that Frank doesn’t run off. The restless tone still dominates these scenes, but simultaneously, Bill’s seemingly character-defying (in)actions begin to compound into one central idea that even in the apocalypse, even when everyone is struggling to survive and dependence on others equates to weakness, trust and solace can still be found, and this idea is most prevalent in the piano scene.

Bill’s entire existence mocks the apocalypse. Others struggle to find resources, but not Bill; Bill’s got unlimited food, safety, and comfort. While he fortifies his property, the songs that accompany him are “I’m Coming Home To Stay” and “White Room,” two rock songs that basically taunt the eerily atmospheric soundtrack of the rest of the show. The piano, however, juxtaposes both the rest of the world and Bill’s fortress. In an apocalyptic world where people fight everyday for food, there is no room for the piano, and in Bill’s pragmatic fortress where everything serves a practical function, the piano sticks out like a sore thumb because it represents something that has no right nor purpose to exist in the world of The Last of Us: ART, and equally as incongruous as the piano’s existence in the apocalypse is Bill’s zealous appreciation of it. When Frank asks Bill about the piano, Bill says that it’s worth “currently nothing,” but as Frank begins butchering “Long Long Time” Bill repulses, and in reaction, abruptly stops Frank as if to suppress the artistic frustration inside of himself—but Frank pulls him in. He tells Bill to play, and Bill does the unbelievable: he turns his back. And what ensues is my favourite scene of anything of all time.

I remember watching this scene for the first time. I remember there was one particular shot that explicitly framed Frank standing tall while looking at Bill’s exposed and vulnerable turned back. I remember thinking about how this scene directly inverts their initial encounter of Bill looking down on Frank in the hole. I remember fear—thinking to myself that this was Bill’s mistake and his moment of peripeteia in which upon turning his back and showing vulnerability, he commits taboo in regards to both the apocalypse and his personal set of cautious values, and Frank will surely now bring down his scythe, punishing Bill for growing lax… But once the music started and first three chords played, I knew immediately that everything will be alright.

The apprehensive tone doesn’t stop with the piano scene, because while the fear that Frank will betray Bill disappears, it’s immediately supplanted by a fear far greater than betrayal: the fear of loss.

When raiders siege Bill and Frank’s home, the scene isn’t scary because raiders are attacking, it’s scary because Frank might lose Bill.

When Bill and Frank share strawberries, the scene is just as beautiful as it is tense because the fear of loss is eternal whilst the sweetness of the berries, temporary.

And when Frank becomes terminally ill, the fear of loss becomes a reality more real than ever. Bill’s vulnerability is no longer just his back, rather, that vulnerability has manifested itself into something far rarer and fragile: a lover. And in the end, faced with losing his love, Bill chooses to commit suicide alongside Frank, an act that should technically end all possibility of future purpose in their lives, but given the transformation of their deathbeds into their wedding beds, serves in actuality to give meaning to their lives through their deaths. Henry dies in distraught—Bill and Frank die in pride.

Corroborating this post-mortem purpose, the last shot of the episode zooms into their turquoise room, adorned with plants and art, comforting the audience by telling them that Bill and Frank have left their mark and are in a better place now overlooking Joel and Ellie. Of course, there is no guarantee of heaven, and for all anyone knows, the death of Bill and Frank marks the end of their times together along with any hope of finding purpose in the future; nevertheless, the leaves will eventually fall, flowers will wither, paint will dry, and people will die. Thus, to Bill and Frank, there’s no better way to rebel against this absurd and impermanent world than by celebrating one’s existence no matter how temporary those celebrations may be.

Beauty, love, and passion create anxiety, tension, and fear, but regardless of whether you’re struggling everyday to survive or you’re living lavishly like Bill, death is inevitable, and although it serves as the end to all memories and purpose in life, its impending presence paradoxically gives life its meaning by assuring a conclusion to everybody’s story.

Apocalypse

In the middle of winter I at last discovered that there was in me an invincible summer.

Return to Tipasa, Albert Camus

The Great Plague lasted for only a little less than two years. The eventual containment of the outbreak was the result of a combination of quarantine, sanitation, herd immunity, and other practical interventions. But both ironically and unironically, despite the devastation the bubonic plague caused, if the recent history of Covid-19 has proven anything, it’s that people will make the same mistake over and over again, and even with new, groundbreaking scientific discoveries that promise a better, more logical future, the absurd will always be everywhere, indifferent to the order and chaos of the world. The Last of Us aims to expose this bitter truth. An innocent girl is murdered in a fit of confusion, a loving brother dreams of a hopeful tomorrow one day yet takes his own life the next, and a malevolent preacher exploits the vulnerable, only to be rewarded by loyalty and reverence. But at the same time, a directionless friend can die happy with their loved one, free of their duties to serve a meaningless greater cause; an alt-right man can discover love in a gay relationship; and a passionless father can find purpose to endure and survive even in the hopeless apocalypse. Suffering will not end, pain will not end, and death will not end, but so too, will the freedom to challenge the absurd not end, and for characters of The Last of Us: in the middle of the apocalypse, they at last discover that there is in them an invincible salvation.

Leave a comment