With over 1.5 billion streams on Spotify, “Glimpse of Us” epitomizes Joji’s triumphant metamorphosis from Filthy Frank—except the song’s not his.

Table of Contents

We Fall Again

September 27th, 2017: George Kusunoki Miller releases his final video, “FRANCIS OF THE FILTH,” on YouTube, marking the end of the TVFilthyFrank channel. 20 days later, he debuted the single “Will He” on Spotify and iTunes, marking the beginning of Joji.

Throughout most of the early-to-mid 2010s, the melancholic artist we call Joji today presented himself in a far less melancholic fashion through his YouTube persona: Filthy Frank1.

Filthy Frank was not a guy whom you’d imagine “Slow Dancing in the Dark” or willing to “Die For You” as Joji does. No, Filthy Frank was the guy who’d popularize the Harlem Shake meme along with releasing other cinematic masterpieces including but certainly not limited to…

- Playing Recorder with Nostril

- Pimp my Wheelchair

- 2 Girls 1 Organ

- Nut Blast

- Illegal Crawfish Racing Olympics

- Human Ramen [take a wild guess what this video’s about]

- Vomit Cake [yes, he eats vomit]

- Pink Guy – Hitler’s Evil Son

Filthy Frank was what some would call an “anti-vlogger,” a creator who’s content critical of other vloggers and strives to challenge the monotony of content creation through the weaponization of satire. Yes, that was it! Filthy Frank was a GENIUS! An anticultural pioneer and a hero to all who were too smart for the Logan Pauls and Casey Neistats!… But let’s be real, with videos like “Porn Title Rap,” he was for the most part just a troll, and the vast majority of the audience he was a hero to were just edgy kids and Redditors.

But sometimes, he was more

On January 4th, 2017, Filthy Frank released the album Pink Season under the “Pink Guy” character, one of the many alternate personas Filthy Frank assumed. As expected, the 35 songs2 of Pink Season were vulgar and included the likes of “STFU,” “D I C C W E T T 1,” “I Will Get a Vasectomy,” “Hentai,” “Uber Pussy,” and “セックス大好き” (which translates to “I Love Sex”). However, on Spotify, nestled between “SMD” and “Club Banger 3000” is the one minute and forty-two second song “We Fall Again.”

At around 77bpm and played in an ethereal C major, “We Fall Again” stands out in the album as one of the slowest songs of the catalogue. Pink Guy isn’t screaming or fast rapping or moaning at the mic, but rather singing with what seems like genuine, unironic authenticity. Likewise, in contrast to the other songs that include lyrics about being sexually attracted to Donald Trump, iCarly, and Dora the Explorer (yes, there are three separate songs each about wanting to bang one of those characters), the lyrics about falling in love in “We Fall Again” are sincere, dignified, and abnormally normal:

Uh, when you turn around, I lose vision)

Got me running deep in the superstition, and I

Can’t believe my fucking eyes (I’m done, quit, I’m done, yeah)

Yet a thousand years, I never thought I would see you come from beneath me

I feel like falling (falling)

I feel like falling (oh)

Excerpt from “We Fall Again”

There were a number of reasons why George Miller left Filthy Frank. Filthy Frank was taking a toll on George’s mental and physical health, he wasn’t enjoying making videos as much, YouTube kept demonetizing his content, and he wanted to focus on launching his music career as Joji. By the time “We Fall Again” released, all of those reasons had been long present, and it’s in this specific song do we see the first glimpses of Joji. In complete juxtaposition to Pink Guy, “We Fall Again” features no satire, no joke, no irony or comedic appeal so deeply embedded within the literal name of Filthy Frank; and without the filth, Frank is just Frank, a regular guy like George. However, despite juxtaposing the character of Filthy Frank and Pink Guy—the personas that Joji renounces, regrets, and refuses to discuss as much as possible—it’d be completely erroneous to argue that “We Fall Again” is the real George Miller.

George had confirmed that at least during the later stages of Filthy Frank, he had only continued for the revenue, and once that revenue—along with his health—grew inconsistent, so too did his motivation to make more TVFilthyFrank content. Viewing Filthy Frank from this corporate perspective, it’d be fair to argue that Filthy Frank was just a job and Joji is the real George fuelled by deep passion and love for his work beyond shallow financial gain.

But in this ********** world, the artists can’t be separated from the worker.

When Joji released In Tongues in 2017, it quickly became a commercial hit featuring songs like “Worldstar Money” and “Demons” that eventually reached hundreds of millions of Spotify streams. By that metric, the immediate stardom of Joji validates George’s successful departure from YouTube and smooth transition from video producer to songwriter. However, five years later and with the release of his album Smithereens in 2022, Joji fell once again into the cycle of corporatism Filthy Frank had been victim of.

The songs in Smithereens were a lot less “Joji” and a lot more 88Rising, the studio that signed Joji during his genesis in 2017. By the time Smithereens began production, Joji and 88Rising had begun fighting over creative control of his music, and considering that eight of the nine songs of the album were ultimately written by ghost writers instead of Joji, it’s safe to argue that Joji lost the creative fight—but not without his Hail Mary manifested in the song “YUKON” in which he denounces 88Rising through the concluding lines: “My voice will be their voice until I’m free / My hands will be their hands until I’m free.”

Neither of the album’s two more streamed songs, “Glimpse of Us” and “Die For You,” were written by George.

Once again, George had lost his voice.

Crash Course Clowns

Although modern clowns have been reduced to Pennywise and mockery emojis under Instagram comments, they used to serve a more serious, less comedic, purpose in society.

It takes wits to make a good joke. It takes nuanced linguistic application to make a good pun. In the Medieval Ages, the skills to write a joke professionally were reserved for the literate, many of whom were failed clergymen banished from the church yet carrying with them their literacy and will to survive by whatever humiliating means necessary. Hence, with no pride to their name, these disgraced individuals turned to jestership for survival through entertaining and bootlicking kings. However, in their quips of self-mockery and tomfoolery were also instances of societal mockery. Clowns were clever and knew the ills of the world and how to make comedy out of tragedy and exploit the moment whether for laughs or for gain or for a combination of both. Due to this weaponization of satire, clowns found themselves as archetypical truthsayers in literature.

Shakespeare’s clowns are smart, oftentimes the only characters able to take an objective third-person perspective on the story at hand from observing Romeo’s love as infatuation to Othello’s as obsession. Likewise, in Goethe’s Faust, what would be a more fitting character for Mephisto, the literal Devil, to manifest than a Machiavellian court jester who corrupts the king into inventing modern **********?

Filthy Frank fits this tragicomedic view of clowns as sage figures. He’s tragic for hating his own existence, comedic—at least to some—for masterpieces such as “Please Stop Touching My Willy,” and honest and wise as depicted through his satire against the overindustrializing, ad-safe YouTube scene.

Unfortunately for the jesters and Joji, the complexities of clowns would only shallow in the 19th-century.

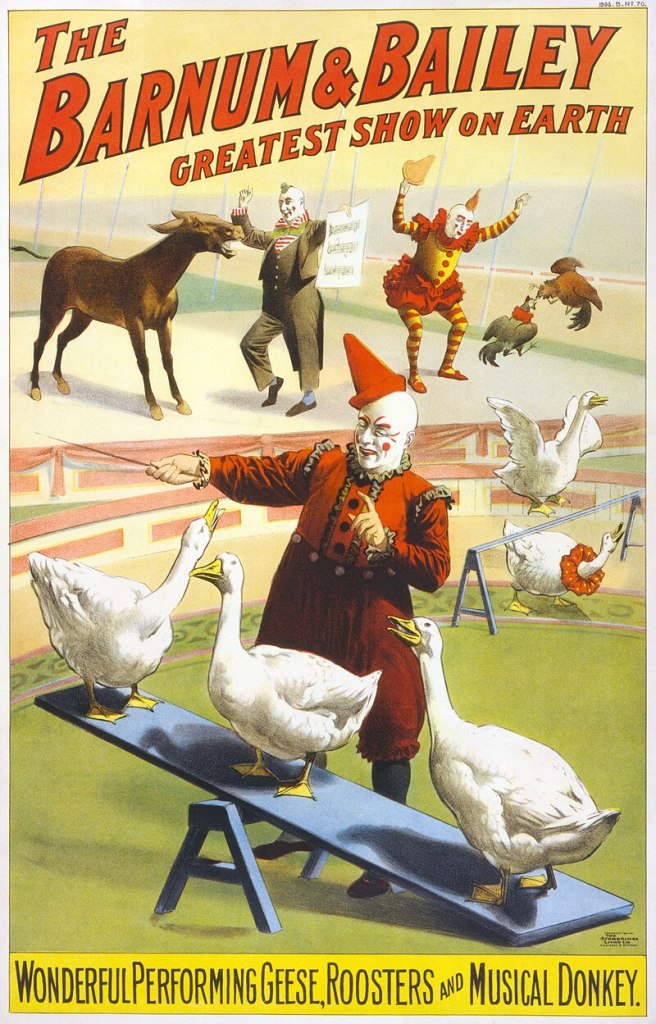

Due to the decrease of feudal courts and increase of public entertainment demands, court jesters found themselves as circus clowns. Despite literature’s depiction of jesters as clever truthsayers such as those presented by Shakespare and Goethe, to 19th-century monarchs eager to prove their etiquettes superior from one another, the satire and jokes of jesters didn’t end at the message, but at the laughter. So jesters became clowns.

Unlike court jesters, circus clowns weren’t failed clergymen blessed with the exclusivity of literacy. Instead, it was performers like jugglers and actors who usually became clowns. Consequently, the goal of clowning shifted from social satire and entertainment to solely entertainment—but not necessarily all for the worse.

The reduction of clowns into pure entertainers also reduced the exclusivity of the clown’s audiences. Court jesters might have been more critical and complex with their roles, but those qualities also gate-kept their appeal to the aristocrats alone. In contrast, the tomfoolery of circus clowns appealed to the entire middle class, particularly children.

After World War 2, popular mascot clowns such as Bozo and Clarabell would become emblematic of post-war American entertainment. With the introduction of television, clowns became ever less personal and ever more artificial, but they nevertheless carried a positive connotation of child-appealing joy and whimsy… until America’s happy postwar zeitgeist turned sour… oh, and there were pedophiles too.

As the Vietnam War began and its atrocities were publicized by radios, American pop culture lost its innocence. Because the media started turning its lens towards burning bodies, massacres, and protests, Americans grew cynical of institutions such as entertainment culture. The juxtaposition between America’s war crimes in Vietnam and happy-go-lucky entertainment at home resulted in Americans perceiving icons such as clowns to be shallow and manipulative for capitalizing off of blissful ignorance in a time of devastating crisis. Even after the Vietnam War, the disillusioned American people would remain media critical of entertainment and advertisement culture.

Ronald McDonald? The jolly clown who gives out Happy Meal? Happy? What can possibly be so happy in this sad sad world >:(. Can’t you see, stoopid? McDonald’s is only trying to make kids happy because Big Burger wants to siphon money out of your wallet! They never cared about the happiness of your Ignorantly Happy Meal! They’re just after the kids!!…

And so was John Wayne Gacy.

This blog post will not be going into detail regarding what Gacy (better known as Pogo the Clown) did because it is extremely triggering. I will link his Wikipedia article, but specific details of his actions aren’t important for this post. All that needs to be known is that Gacy worked as a clown and was a pedophile who was arrested in 1978 before being sentenced to death (you can probably entail the trigger warnings from that description).

After Pogo’s crimes and arrest, clowns became universally alienated and villainized by the American purview. To the cynics, clowns had been and will continue being symbols of artificiality and overconsumption. To the parents, clowns were now probably one of the last things you’d want around your kid. Hence, having been incapacitated of their ability to deliver satire, humour, and joy, clowns found new purpose by evoking horror instead.

In 1986, 8 years after Pogo’s arrest, Stephen King released the horror novel It, which presented its clown Pennywise as a literal grotesque alien who eats children and uses his clowning shenanigans to lure, torture, and murder his prey.4 2 years later, in 1988, the horror movie Killer Klowns from Outer Space would be released and was about (believe it more not) killer clowns from outer space. Another 2 years after Killer Klowns, It would receive a film adaptation in 1990 before being rebooted in 2017, standing testament to the staying power of the killer clown image over three decades.

In ironic fashion, after two centuries of losing their truthsayer reputation, the clown’s once-respected complexity would once again be acknowledged, but as horror, not satire. With no audience, clowns were stripped of their court and circus and children’s television contexts; and without those contexts, all that remains is a man wearing uncanny make-up whose true emotions stay forever undecipherable. All that remains is someone who can see you for who you are, but you can’t see them. All that remains is the unknown—the horror.

Eventually, scary clowns fizzled out of media because people just grew fatigued from hearing about a “scary clown sighting” for the millionth time in October. Today, clowns have become insults. If someone says something stupid or corny, you quote them word-for-word under the comment section with clown emojis spammed at the end to show the world how foolish their words are. They’re just a joke! They’re just a clown whose existence should not be taken seriously—not as satire, not as the entertainer, not as horror, but as the joke itself! Tra la la, bitch! 🤡🤡🤡

However, throughout the scary clown era, another paradigm of clowns emerged: the tragic clown. As television and radio beget a more homogenous pop culture, mass media also popularized the idea of the tragic entertainer. Pop culture icons such as Marilyn Monroe, Jimi Hendrix, and Kurt Cobain died young, bringing their genius to an abrupt end. Paired with the media-critical lens publicly introduced during the Vietnam War, entertainers became seen as entangled with tragedies such as childhood trauma, drug-abuse, and mental illness. Because clowns were metonymic icons of general entertainment culture, all of these tragic qualities were attached to the idea of clowns.

They don’t wanna be your joke! They’re just working to get by in life! Man, I bet they’re crying behind all that make-up (that’s what the point of the mask is!). These entertainers make you happy while they’re sad—this is so sad! (Fun fact: My mom literally told me all that when I was a kid.)

All of a sudden, the role of clowns in society partially circled back to their initial court jester roles of social commentary. After two centuries, through characters such as Joker (namely Heath Ledger’s Joker), Tyrion Lannister, and Hisoka, the clown redeemed its character nuance as wise (though often misguided) truthsayers in corrupt societies (we live in a society!). Moreover, with Joaquin Phoenix’s 2019 Joker winning best leading actor and being nominated for best picture at the Academy Awards, clowning has also reclaimed its prominence amongst the elite.

The history of clowns reflects the malleability of entertainers at the hands of technology, economics, and war. Clowns change, adapt, and become what they need to become to survive. However, when being what one needs to survive entails the removal of character complexities that one can truly become, the history of clowns reads not about malleability nor survival, but rather about subjectivity and the inability to be yourself while under the spotlight of mass entertainment.

Alienation

As Filthy Frank, George dealt with disinterest. As Joji, George dealt with alienation. As both, George battled against capitalization issues, whether it was because of YouTube demonetizing his videos or 88Rising corporatizing his creative process.

Filthy Frank’s satiric and obscene videos—that is art! Joji’s euphoric and melancholic songs—that is art! And art is George. George is creative. From the vulgar to the earnest, George forces himself to create because creation is his identity. However, in our profit-driven world (guess the synonym!), art cannot exist outside the choking grasp of monetization. Yes, most art is created without financial incentives from the artist; children scribble with crayons all the time without thinking about their creation’s ability to put food on the table. Likewise, yes, nature is art, and so is literally everything else in this universe so long as you look at it under the right perspective. But nevertheless, for social media, television, books, popular music, and other artistic media that require any sort of financial institution to exist, money is their lifeblood.

I love Joji’s music video for “Sanctuary.” It’s fun, tells a story, and weird in an almost Filthy Frank fashion. Simultaneously, the video is only made possible thanks to the actors, make-up artists, camera crew, and other paid contributors, including 88Rising who funded the entire production.

The existence of money and 88Rising aren’t all bad for Joji, as both the incentive and incentivizer have given him the opportunities to grow his audience and assure his artworks are allocated the utmost resources to flourish. But as observed in Smithereens, when the end goal of that flourishment prioritizes the investors’ profit over the artist’s vision, then the artist just becomes a worker. And the art just becomes a product.

Severance, Severance

Slightly unrelated to Joji, there are two works of literature both about the doppelganger effect between one’s personal self and work self. Incidentally, both are also called Severance!

Ling Ma’s 2018 novel Severance follows the story of Candace Chen who’s stuck in a pseudo-zombie apocalypse except instead of flesh-eating monsters, the zombies of Ma’s Severance are individuals who have caught “Shen Fever,” an infectious disease that severs people’s personal life from their work life and condemns their body and mind to mindlessly repeat daily work without personal agency. By associating the horrid connotation of zombies to Shen Fever, Ma characterizes ********** repetition as dehumanizing and meaningless. Candace isn’t infected with Shen Fever, but in a Kafkaesque fashion, she—like Gregor from The Metamorphosis—chooses to continue work as usual despite nearly everyone in her city becoming frickin’ zombies. Matter of fact, it would be inaccurate to say she “chooses” to work because she doesn’t “choose” anything. She just… works… with neither passion nor reluctance. Even without Shen Fever, Candace had already been programmed by the world into a zombie.

Her boyfriend left her alone while she’s pregnant. She constantly reminisces about her hometown in China. America’s been zombified, rendering money effectively useless. But still, she works solely out of habit until the company she works for shuts down and promptly terminates her. After all, there’s no reward for loyalty.

Similar to Ma’s Severance both in name and premise, the 2022 show Severance created by Dan Erickson also explores the alienation between person and worker. In Erickson’s Severance, employees at Lumon, an Apple-esq company, go through a severance procedure, which creates a second identity for just the worker called an “innie.” Innies have no memories of the outside world—no memories of their “outie’s” life—and vice versa. New memories are created by both innies and outies until eventually the two personalities change into completely different persons.

Erickson’s main inspiration for the show was his own desire to escape the 9-to-5 monotony of work. He wanted to just get work over with as the severance procedure had enabled the characters to. Like cutting out part of a video clip then stitching the rest back together, outies would drive to Lumon at sunrise then immediately see the sunset as they head home having skipped all the time and memories at work in between.

The past Erickson didn’t see a problem with the procedure, because to him, work was just the means to an end and not a part of the Dan Erickson identity. On the other hand, the modern Erickson sees work as an entirely separate identity equivalent to the personal ego.

The outies and innies experience different events, make different memories, and build different relationships. As an outie, the protagonist Mark grieves the disappearance of his wife. Meanwhile, as an innie, Mark finds his first love and re-loses his virginity while ignorant of his outie’s marriage and obsessive sorrow.

The outies and innies fight and bicker. In the second season, the two Marks directly argue against one another over their romantic values, and in the first season, one of the innies attempts to commit suicide in an effort to murder her villainous outie.

In contrast to Ma’s zombies, Erickson characterizes the worker not as mindless but as fully humanized individuals. From the perspective of Erickson, Ma’s depiction of work-life severance fails to capture the unyielding humanity behind every worker no matter how alienating their work may be. The innie affects the outie as depicted through Candace’s abandonment of love and culture for the sake of work; similarly, the outie affects the innie as exhibited through outie Mark’s selfish intention to quit his job and effectively murder the relationships, memories, and identity of innie Mark. Both innies and outies are just as consequential to one another, and ultimately, with their love, struggles, memories, and more, the innie is never just a worker.

We All Float Down Here

Filthy Frank and Joji are both victims of a system that prioritizes profit over artistry, and whether it’s YouTube deleting his videos or 88Rising usurping his writing, George’s initial vision will forever be deformed by the industry’s molds until his art and work become severed into George, Frank, and Joji—both outie and innies left inautonomous just as the clerics who were severed into court jesters were severed into circus clowns were severed into marketing devices to horror archetypes to internet mockery.

Undeniably, work in our ********** society inevitably severs the artist from their creations. As such, it’s easy to just say that Frank and Joji aren’t the real George or that the clowns today aren’t the real clowns. But this juxtaposition betrays the innie’s humanity and the artist’s indomitable spirit to create despite perpetual oppression. Although the severance of art and work remains ever-reductive, the severed—both outie and innie—are nevertheless two sides united in one’s identity. Both are equally real and authentic. Both are equally subject to all the world’s suffocating pressures.

We live in a sad fucking world. We all wanna “be ourselves” and “follow our dreams” and whatnot, but for the vast majority of us, those are impossibilities. Joji, despite his escape from Filthy Frank, can’t rewrite the world’s ill structures just as the court jesters are unable to pass laws and decrees despite their bountiful wisdom regarding the monarchy’s failures.

Sometimes, I walk into a McDonald’s and see some miserable worker who very obviously doesn’t want to be there. Then, I remember that I’m hungry and order a Big Mac.

I still get hungry. I still need to work for money just as Joji still has to release music under 88Rising and clowns still have to keep lobotomizing their identities to match the world’s entertainment paradigms and demands.

When I was in elementary school, one of the most repeated quotes from my Grade 5-7 teacher was “be the change you want to see in the world” by Gandhi.5 Maybe this is what this essay is about; I’m writing on the topic of ********** and alienation in hopes of people reading it and changing their mind just a little. Inevitably though, even with this essay’s existence, I’ll return to school and then get a job and then work and then probably watch parts of myself start reflecting that McDonald’s employee. Through sharing this blog and other means, I can maybe rewrite a few words of this failing book that is our world—but I can’t rewrite the whole book—and even with the help of hundreds of millions of other people manifesting change, it’s unlikely that I’ll live long enough to witness and reap the rewards of its final, fully-edited publication.

But I don’t want to be miserable. I don’t wanna to live my life despising everything I do and shaking my fist at things I can’t control. I don’t want to perceive my innie’s life as a condemnation due to **********’s flaws. Surely, George doesn’t want to see his career as a series of artistic failures permanently tainted by inescapable subjectivity. In Erickson’s Severance, the severance procedure serves as a symbol for work alienation, but regardless of that symbolism, innie Mark is undeniably alive, and therefore it is the outie’s responsibility to respect his innie’s existence and learn to negotiate with this deeply dysfunctional system.

The clowns are jokes now. Frank is gone. Joji is a puppet. We all have Shen Fever. Everyone is severed. Humanizing the innie is just a coping mechanism to conceal the ugly state of alienation and subjectivity we share.

But for now, that cope will just have to be enough.

Footnotes

- On the TV FilthFrank channel, George had multiple personas including Pink Guy, Salamander Man, Chin Chin, and more. For the sake of simplicity, I will be calling him Filthy Frank throughout most of this blog other than when I discuss the Filthy Frank album, which he specifically released under the Pink Guy persona. ↩︎

- On Spotify, iTunes, YouTube, and Google Play, the album now only has 33 songs because the other two were removed likely because they were too filthy even in comparison to the other songs. ↩︎

- Maybe this quote is from this book. I dunno though; I retrieved it from Wikipedia, which cites that book lol. Regardless of the source’s validity, the paintings message and description still stand. ↩︎

- Yes, there was The Poltergeist in 1982 and a plethora of other scary clowns before Pennywise. But let’s be serious, none are as iconic as Pennywise. He’s just him… or should I say it? 😉 ↩︎

- This quote is actually a misquote from something else Gandhi said, but because his original quote effectively delivers the same message and for the sake of this paragraph’s brevity, I’m just going to use the more popular, shorter phrase. ↩︎

Leave a comment