Japan is living in 2050! They got robot waiters, conveyor belt sushi, vending machines at every corner, preheated toilet seats that warm up your ass… and one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

If someone were to offer you an opportunity to start a completely new life in another world absent of school, work, possessions, friends, and family, would you take it? I’d assume no… of course not! Who would voluntarily abandon literally everything around them and curse themselves into a world where they’re eternally plagued with the knowledge of what they’d lost in their previous life. And yet, the ironic rise of the isekai genre says otherwise.

The genre isekai roughly means life in another world, and its popular works include Alice in Wonderland and Spirited Away, both of which feature protagonists who’re transferred into another world and are thus on a quest to find their way back home. However, over the past few decades, the genre has become more degenerate, so to say, especially in its hyper-fetishization of life in another world as seen in anime like Konosuba and No Game No Life, in which protagonists are given special powers, high status, and entire harem lineups in their new worlds. Even in darker isekais like Re:Zero and Mushoku Tensei, the supposedly struggling protagonists still, without a doubt, live more eventful and meaningful lives in their new surroundings as opposed to icky icky Earth. Unlike Alice in Wonderland and Spirited Away, modern isekai protagonists do not reject their new worlds, but are rather quick to accept it as their new home—a superior home.

Culture

Now, in the most over-simplified explanation possible, the rise of the isekai genre is the result of a desire for escapism—wow, go figure! But then there’s a layer of irony to this. Japan has the third largest economy in the world, their people are renowned for their good work ethic and quality of life, you go on TikTok and everyone and their moms are talking about Japan’s cute culture and futuristic tech.

With all this in mind, it’s kinda confusing why one of their most popular television genres at the moment literally centres around escaping this seemingly utopian life. Well, TL… DR, it’s not a utopia, because while the amenities listed above look heavenly compared to the boring West, the school and worklife of Japan is absolute hell. From elementary school, students are constantly pressured by parents, peers, and institutions to get as high of a mark as they can so they can get into a good middle school where they can repeat that exact same process to get into a good high school so that they can get into a good university so they can get into a good job so that they can get into retirement so that they can die. Admittedly, modern Western education paradigms are also quite similar with university being the be-all and end-all of “success,” but where the two cultures differ is in sheer intensity: Japanese students are expected to stay at school from sunrise to sunset, exam scores are nakedly exposed on boards for everyone to praise and ridicule, and by no means does life get better after graduation.

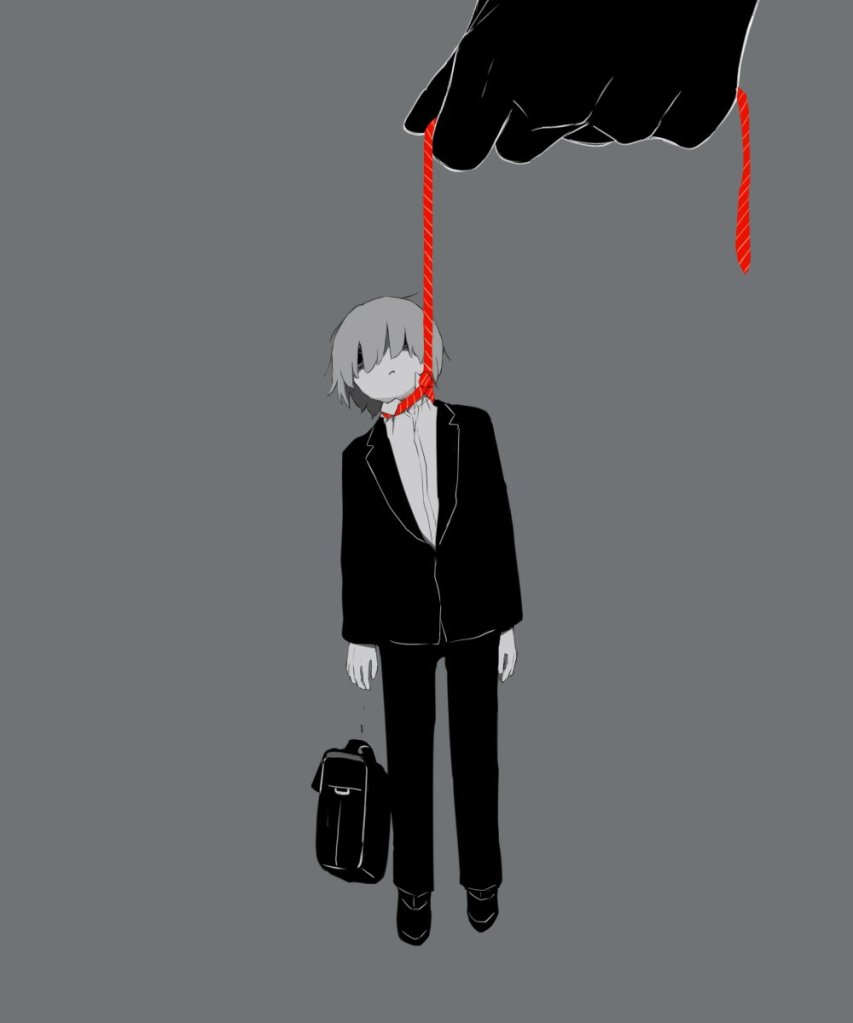

Coined in 1978, the Japanese term “karoshi” translates to “death by overwork” (yes, they had a need for this word to exist). On a daily basis, Japanese salary workers work upwards of 14 hours a day including unpaid overtime. They’re contradictorily expected to conform with their fellow employees whilst also competing with them in toxic work environments. Those who can’t withstand these expectations either die under pressure—whether that be via suicide or other health concerns—or get labelled as useless NEETs to society.

I know these societal issues aren’t exclusive to Japan, and the Japanese government has tried to remedy the situation (to a failing extent); however, there is nevertheless a huge mental and physical health crisis that’s formed from old feudal culture and other factors such as war and economic recessions and the government is making an attempt to fix it but it’s kinda a crappy attempt and people aren’t following the new guidelines-

A degenerate subculture is born.

Degeneracy

The following are all real isekai manga/light novels:

- That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime

- I’ve Been Killing Slimes for 300 Years and Maxed Out My Level

- Do You Love Your Mom and Her Two-Hit Multi-Target Attacks

- Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon?

- My Reincarnation as a Hot Spring in a Different World is Beyond Belief ~ It’s Not Like Being Inside You Feels Good or Anything!?

I don’t think anyone would argue against me if I said that, as it currently stands, isekai is one of the most degenerate popular genres of any medium—and isekai authors are fully aware of this. Degeneracy forms the foundation of isekai as the genre constantly tries to appeal to its degenerate audience base. In most isekais, before the protagonist is sent off to their new, better world, their life is degenerate, pathetic, and/or mundane. In Re:Zero, before Subaru became a hero in his new world, he was a shadow of his father and a disappointment to the eyes of all. Likewise, in Mushoku Tensei, before the nameless protagonist is reincarnated as Rudeus, he was a pathetic, repulsive otaku who originally died shortly after being caught masturbating in his room.

Even characters who’d lived presumably admirable lives don’t appear to care whatsoever about the decades they’d spent in their previous worlds. Despite once being a successful and passionate doctor, Aqua from Oshi no Ko has little interest in discovering the means of his reincarnation and even admits to feeling depressed whenever he thinks about his previous life, a feeling shared by Rudeus who actively tries to forget his previous name. Needless to say, isekais and the satisfaction of life amongst its audience follow an inverse trend: as people grow less and less satisfied with their lives, isekais grow more and more in popularity, succeeding by feeding off people’s failures.

So far, I’ve made a lot of insulting comments against isekais and its audience, but of course, if me writing this blog post about isekais serves to prove anything, it’s that I do enjoy watching them (like, I don’t just binge a 24-episode show while shaking my fist going all “grrr, boy do I hate isekais! We live in a society!”). And while I fortunately can’t relate to the pathetic lives of many isekai protagonists, I do, however, guiltily enjoy the shows as power fantasies. I wish I was smarter, I wish I was stronger, I wish I was better-looking, I wish I had unlimited rizz,

I wish…

I wish…

I wish…

I wish…

I wish…

I regret.

Wish Fulfillment and Power Fantasies

A LOT of media play with this idea of wish fulfillment and power fantasies. Everyone wishes they’re as strong as Spiderman, as clever as Light, and as special as Neo. The first book ever written that humans currently know of is The Epic of Gilgamesh, in which Gilgamesh, despite becoming a wiser and humbler person by the end of the book, still starts off as a power-hungry king who’s able to steal, murder, and rape whatever and whomever he so desires. Today, you go on any social platform and you will, eventually, see posts about being a sigma male, being popular, being whatever it is you are not. Influencers like Andrew Tate succeed by preaching and promising their power fantasies. They preach about the money they’ve earned, preach about the women they’ve banged, preach about the work ethic they’ve created, preach about… a better you.

But what’s wrong with that?

I mean, yeah, people like Tate have undeniably perverted the ideas of self-improvement thanks to the whole misogyny, narcissism, disinformation, and child-trafficking thing, but the fundamental goal of becoming a better person really has no blatant flaws to it. Miles Morales is relatable, and his journey to become a better Spiderman is one that people should look up to. Gilgamesh learns to become a wiser and humbler king by the end of his epic. Luffy, Naruto, and Ichigo—although given supernatural powers—all have their hearts in the right place and have trained hard to protect those they love. Hell, even Subaru is an aspirational figure; his anxiety is relatable and his triumph over it is definitely inspirational and worthy to be looked up to. And yet, there’s still something destructive about the isekai genre, because while Spiderman and One Piece depict characters overcoming their conflicts through rigorous and earnest effort, the solution that isekai proposes is an opt out of life itself.

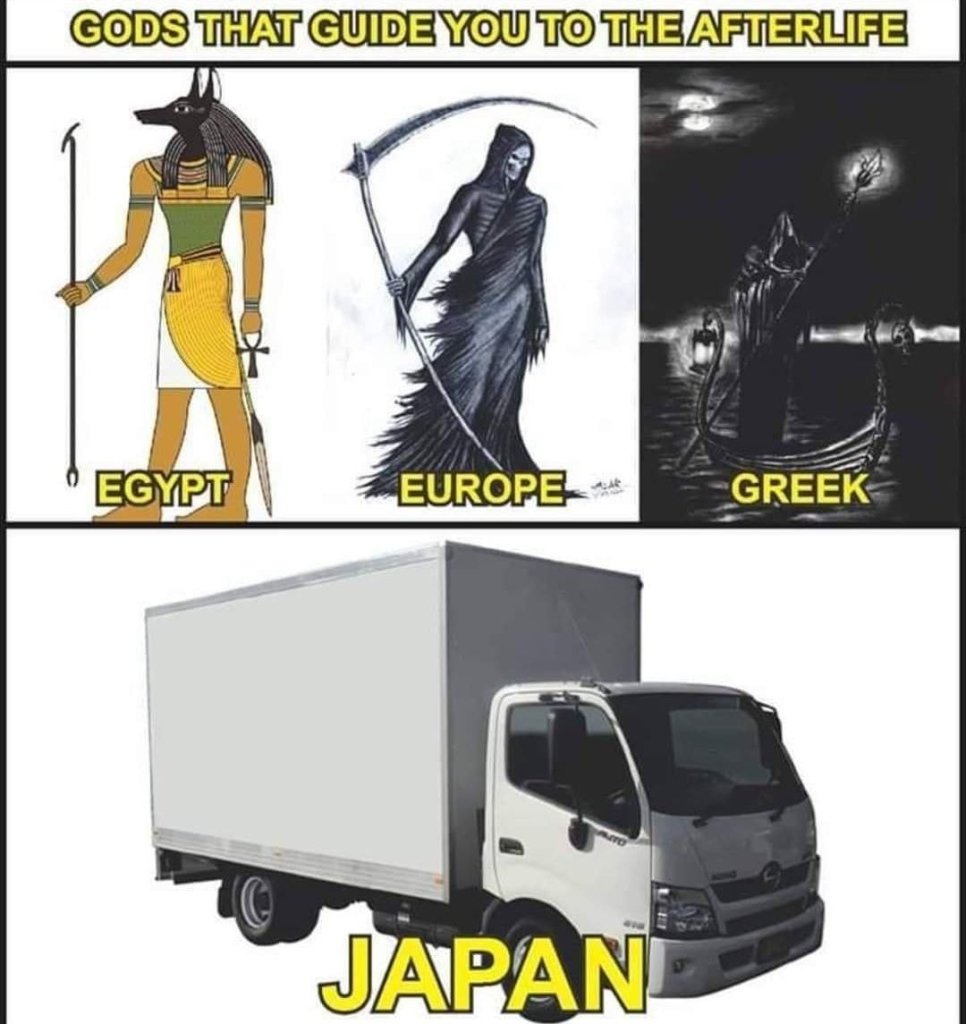

There’s the meme that “truck-kun will isekai you,” and I think this meme acts as the perfect symbol for the genre as a whole. It’s a genre in which the solution to the problems in your current life can be fixed by an uncontrollable factor. From the isekai perspective, dying, abandoning everything in life, getting hit by truck-kun isn’t grim—it’s a blessing—and no other popular genre even comes close to this overt fetishization of death and escapism, which is made increasingly more concerning by Japan’s ever-growing suicide epidemic. People wanna escape, and the power fantasies so abundantly provided by media serves to fill that hole, but isekai extends beyond just power fantasies. More than venerating the transformation into someone better and stronger, isekai fantasizes the departure front the pathetic, the mundane, and the world itself.

The Road Not Taken

“The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

(1915)

I wrote a timed essay for this poem once. The first time I read it, I noticed the speaker’s regretful tone at the end regarding his decision on which road to take, and yet, once I began writing my essay, I opted to write about how his decision to pick the less-travelled road was the better choice. I had ignored the clear signs that he regretted choosing this road because media around me fantasized this idea that to be successful and happy, you must be different and pick the path that no one else has. But shit happens, and there’s no doover, and maybe that’s what gives this poem—and life itself—meaning. Sure, Frost ends the poem with a remorseful sigh, but at the same time, he emphasizes the ultimate weight of his choice. Regardless of whether he looks back at the decision with sadness or joy, in the end, the decision—his decision—is a gift all on its own. He’s in control of his own life thanks to his choices that enable his joy and his pain, and as he puts it, “that has made all the difference.”

Not in isekai, though. Isekai asks “what if I took the other road? What if I could ditch all my problems? What if I got to start a new life in another world? What if I had immense intelligence, memories, and knowledge at birth like a video character so that I can bulldoze all difficult choices in life?” These are fun and interesting questions, but at the same time, these questions undermine the gravity of choice by inadvertently telling audiences that “you should regret.” Don’t aspire for self-improvement like Gon and don’t aspire to fix your flaws like Thorfinn, because the bigger issue at hand is your regretful past, the world around you, and whatever else in life that’s burdening you that you can’t control. In the most decadent way possible, the prospect of starting life in another world suggests that the biggest problems in life are not the diverging roads up ahead, but rather behind you: the road not taken.

Me and My World

About a year ago, I went to Taiwan and Japan for six months to work and experience life in another setting. It was fun, and I definitely learned a lot, but I’d be lying if I said that there wasn’t a sense of disillusionment—not with the new surroundings, but with myself. Naively, I went to Asia under the assumption that it was gonna “change me” and help me “find who I am.” To be fair, it did do both of those things, but in less so of a “Whole New World” way and more so in a slow and soul-crushing way. Stripped of my friends, school, and parents, the first thing I learned upon arriving in Taiwan was that Taiwan really did not give a shit about me. Cheap bubble tea?! Cool. Wow, you’re from Canada?! Cool. But that’s it… In my new world, I was still me—me with the same personality, characteristics, and flaws that I’ve always had. Above all else, I needed not the world to change me, but me to change myself.

Yet, this isn’t the reality that isekai propagates. In basically every isekai, protagonists gain new meaning and prestige in their new lives as a result of their fresh surroundings, and this made me ask myself the question that prompted me to write this whole post in the first place: if most people were put into a whole new world, how different would their lives actually be?

Because maybe it wouldn’t be different at all. Being in another world doesn’t fundamentally change who you are. If you’re a lazy, pathetic, incompetent slob, you’re still gonna be a lazy, pathetic, incompetent slob no matter where you are.

Or maybe getting isekai’d would make a difference. After all, there’re new opportunities and clear goals in life that can sprout new meaning and direction, and this newfound purpose that wasn’t clearly present on Earth could act as the ultimate conduit to lead a better and more fulfilling life.

And between these two possibilities I’ve listed, it’s this meaning that serves as the great divider between both paths. Like previously established, Japan is safe and you can definitely survive there easily, but actually living a fulfilling life is a whole other matter, and in this safe, yet pathetically mundane world, there is now a desire for danger and meaning outside of just living another day for another day. As quoted out of context from Aldous Huxley’s novel, Brave New World,

“I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.”

And where the world fails to provide these qualities, isekai steps in to give the most convenient solution… but it’s an impossible solution. I will never spin web like Spiderman, but I can at least try to be just a bit more courageous like Peter Parker. However, I can never expect the world to change itself solely for my sake. I can never expect the world to fix my flaws for me.

I want to start over-

-but I can’t.

There is no life in another world, and even if there is, I’d still be the same flawed and pathetic person I’ve always been. But regardless of the conditions around me, I am still alive. I have choice, and with it, I have regret, and with regret and joy, life and death, I have an everlasting reason to continue living in this world to which I proudly call my own.

Thanks for reading.

Leave a reply to Phyeqh Cancel reply