“There is no prize to perfection… only an end to pursuit” – Viktor

The Chinese word 幸福 (xìng fú) doesn’t exist in English.

Plugged into Google Translate, 幸福 translates to “happiness,” but that just isn’t correct. Sure, when you return home from school in the snowy cold of Winter and your mom surprises you with a cup of hot chocolate, its warmth can be described as evoking both 幸福 and happiness. However, the emotional warmth of knowing that Mother loves you so much as to make you your favourite drink after a busy day at school? Happiness isn’t enough to describe.

It has to be 幸福.

In that sense, the more accurate definition of 幸福 is a combination of happiness, satisfaction, and contentedness, specifically in regards to life fulfillment. Unfortunately though, those words only define the denotative aspects of 幸福, because happiness, satisfaction, and contentedness carry within them the connotations of indulgence, stagnation, and complacency. Happiness comes and goes and builds towards nothing long-term just as satisfaction and contentedness lead only to the abrupt halt of one’s progress in life (whatever progress means 🤷). Meanwhile, the connotation of 幸福 evokes a sense of ultimate life fulfillment that translates the negative “you have stopped now” of the aforementioned three words into the positive “you may stop now.”

Admittedly, as I had discussed in my previous blog post, “A ‘Short’ Essay on Asian Heritage,” English has the malleable ability of absorbing foreign words into its lexicon, and 幸福 is no exception. Perhaps most similar word to 幸福 in English is the Greek-origin word “ataraxia,” which Oxford Reference defines as (please read this in your snobbiest voice possible):

“The state of tranquillity or imperturbability, freedom from anxiety, considered to be one of the desirable results of an immersion in scepticism, and by Epicureans to be part of the highest form of happiness.”

Sadly, Oxford does not offer any examples of how this word is used in colloquial English, so I’ve taken it upon myself to write an example conversation to help my dear readers understand 😀

Bob: Hey dude, long time no see! How’s life been? (tries to dap up Robert)

Robert: (refuses to dap Bob up and instead swirls his glass of red wine) Life? Hmph… It’s been rather… ataraxic.

Bob: (puts his hand down and mumbles to himself) Pretentious asshole.

And pretentious asshole indeed! Basically no one speaking modern English will ever use the word ataraxia outside of an academic context. In contrast, 幸福 is used in colloquial Chinese conversation.

As British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argues, the meaning of words derives from its use. Applying Wittgenstein’s definition to 幸福, neither happiness nor ataraxia can truly equate to 幸福 as happiness carries a different connotation and ataraxia is effectively never used at all in modern English. Moreover, even if English were to assimilate 幸福 into a romanized “xingfu” that can be found in your common dictionary, so long as no one chooses to actually use the word, then 幸福, like ataraxia, will just be cast aside as functionally meaningless.

To adapt the word 幸福 into English, therefore, requires not just denotative assimilation, but also connotative reconstruction—achievable only if the West shifts its paradigms of work, happiness, and purpose. After all, as it stands right now, we live in a 幸福less world.

The Disappointing Accuracy of HBO’s Succession

At first, I was gravely disappointed by the ending of HBO’s Succession.

For those who haven’t seen Succession, here’s a quick plot synopsis of the show along with a description of how each season ends:

Synopsis: Kendall Roy is the son of multi-billionaire tycoon Logan Roy. Throughout the show, Kendall fights his siblings over the succession of the family business Waystar Royco. Of course, Kendall’s net worth is in the billions, but in juxtaposition to the sublime title of “CEO of Waystar Royco,” a couple of billions just isn’t enough.

Season 1 Ending: Kendall fucks up and loses his opportunity to become CEO.

Season 2 Ending: Kendall decides to try overthrowing his father to become CEO.

Season 3 Ending: Kendall fucks up again and loses his opportuntiy to become CEO.

Season 4 Ending (Final Season): Kendall was just about to finally become CEO… but he fucks up again and the position goes to someone else. The camera zooms into his sad face as he walks around the park. Throughout the show, there have been many shots of Kendall walking around all sad before the camera cuts to black and the next episode begins to play. But this time, the show just sort of ends, not because the scene or plot presents itself as a natural conclusion to the series, but simply because there is no season that comes after.

Seriously? After 4 whole seasons, 39 entire episodes, the show just… ends?! Logan dies off-screen in Season 4, Kendall ends the series in the same mental state he ends basically every other episode, and even Tom, the man who alas succeeds Logan as CEO of Waystar Royco, has effectively nothing to look forward to in life besides clocking back into his 9–5 before returning home to his loveless marriage.

Pissed off that I didn’t get some epic Avengers: Endgame conclusion, I went online to see what the show’s writers had to say about the ending. In a Rolling Stone interview, I read that the creator Jesse Armstrong said, “I’ve never thought this could go on forever. The end has always been kind of present in my mind. From Season 2, I’ve been trying to think: Is it the next one, or the one after that, or is it the one after that?”

Are you for real right now? There wasn’t some great plan for how the show ends? You just… ended it because it needed an ending?!

But then I thought about how I’d end the series, and I realized there was literally no other way the story could’ve ended.

In the most pessimistic (but accurate) way possible, Succession is about a bunch of rich people ironically finding all sorts of new and unique means to be miserable. The show exhibits them living in absolute comfort, chilling in their penthouses and private yachts, but equally so, the show reveals none of its characters to truly achieve 幸福 because their endless greed leaves only an endless pit in their hearts.

幸福 is an impossibility in a world where the value of one’s character is measured by the digits in their bank account because 幸福 is an end whereas the money you can potentially make is endless. Consequently, Succession had to end the way it did with literally nothing changing thematically. To give the characters a concrete conclusion (whether happy or sad) would be to paradoxically give them an end to their greed in a world where greed can’t have an end. Eventually, the writers, producers, and viewers grow tired of the Roys and their bullshit. Therefore, Succession ends not because the story merits an ending, but because the show—as a show—needs one.

The Right to Be Lazy

In Paul Lafargue’s 1883 pamphlet, The Right to Be Lazy, Lafargue effectively argues for the necessity of 幸福 in capitalist society. Contrary to his father-in-law Karl Marx, Lafargue sought to fight against the overconsumption of capitalism through criticizing the proletariat, not bourgeoisie.

The Right to Be Lazy begins by revealing the modern over-veneration of work as unnatural and paradigmatic of capitalist excess. Lafargue highlights that “the [Ancient] Greeks in their era of greatness had only contempt for work: their slaves alone were permitted to labor: the free man knew only exercises for the body and mind. And so it was in this era that men like Aristotle, Phidias, Aristophanes moved and breathed among the people.”

As such, the state of 幸福 to Lafargue could be interpreted as the dedication to scholarship and rejection of work once one has procured enough money to sustain a lifetime. In contrast to the modern world of Succession, the paradigms of wealth and success in Ancient Greece had an endgame.

Of course, Lafargue’s article is not free of criticism. Aside from being published over a century ago and the whole glazing slave-owners thing, the article fails to fully explore the relationship between poverty and happiness in poor nations and (admittedly, like his Ancient Greek example) stretches a bit too far when discussing the Bible, my favourite example of which being when Lafargue says that (please read in an a demonic voice) “AGRICULTURE IS IN FACT THE FIRST EXAMPLE OF SERVILE LABOR IN THE HISTORY OF MAN. ACCORDING TO BIBLICAL TRADITION, THE FIRST CRIMINAL, CAIN, IS A FARMER[!!!]” I mean like, what was Cain supposed to do? Starve?

With all that said, Lafargue does make one argument that’s aged like wine, that being his discussion of technology in capitalism. To Lafargue, technological advancements should lead to the easing of the proletariat’s workload. In reality, however, the proletariat has repeatedly found new work despite technology rendering past work superfluous. Altogether, the production of work despite its lack of demand creates excess for the bourgeois who is now forced to overconsume so as to justify the overproduction.

Today, this failure of technology is evident in the advent of A.I., which, despite promising a more convenient future, has ironically displaced the jobs of many (go ask my Comp Sci friends; they’ll tell you all about it) while offering no economic benefit to the average worker. “Hooray!” Lafargue might say, “We did it! A.I. did it! Humans can finally now just chill and discover new hobbies and form new relationships and whatnot! We beat work!” Except, that’s clearly not the case, because at the end of the day, people still need to work to survive just as Cain still needs to eat. No one is demanding to work for the sake of work—they’re demanding to work because the other option is destitute poverty. The proletariat is not at fau-

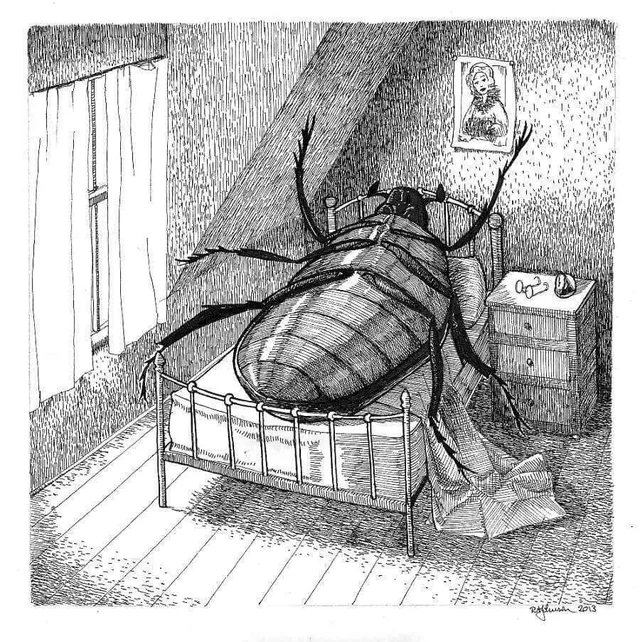

[Human-sized cockroach walks in]

Gregor?!

Okay, so Franz Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis stands testament to The Right to Be Lazy. In The Metamorphosis, the salesman Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to find himself in the body of a bug. Despite his buggy predicament (heh, see what I did there?), the only thing he worries about is how he’d get to work. In simple terms, The Metamorphosis serves as an allegory for the absurdity of work culture, with Gregor serving as the work-obsessed proletariat Lafargue strives to denounce. However, as I’ll once again criticize Lafargue, Gregor shares a lot more in common with the bourgeois Kendall Roy than Lafargue’s separation of the two classes would like to argue. Both characters are engrossed in whatever endless success their work culture promises, and both characters are equally miserable due to said engrossment. As a result, it is erroneous of Lafargue to blame the proletariat for excess work because what Lafargue ultimately criticizes is the paradoxical human flaw of aimlessly desiring financial and purpose fulfillment in a society that has no concept of 幸福.

Final Thoughts

In all honesty, this essay is total bullshit. After all, 幸福 exists in colloquial Chinese, yet judging by China’s constant imperialistic expansions and the unaddressed over-competitiveness of their school and work cultures, China clearly isn’t 幸福. However, I do think it’s apt to use a foreign word to encapsulate a foreign paradigm that, despite our dictionaries’ best efforts, cannot be fully captured without the shifting of the entire culture.

As my Romance Studies professor once said, “when a tree is cut, GDP grows,” and I’d like to think that this unfamiliar perspective of growth and success was what Kendall and Gregor failed to recognize in their endless pursuits.

In the end, only by shifting our paradigms of happiness and success can we end the cycle of excess.

In the end, only by shifting our paradigms of happiness and success can we introduce a world where we could just be 幸福.

Thanks for reading.

Leave a reply to carlo testa Cancel reply